Contrainte/Restraint : New Media Art Practices from Brazil and Peru (Montréal)

Oboro, Montréal

+ Maison de la culture Marie-Uguay, Montréal

From November 7th to December 12th, 2009

The starting point of this exhibition is to show what the Brazilian and Peruvian contexts, in their cultural, social, and political aspects, have in common regarding the use of media technologies. It explores how these aspects are reflected in representative new media art practices and works from both countries. The common issues in these specific contexts could be explained or made visible in a dynamic of dualities, paradoxes and a superimposition of different worlds, which built on idiosyncrasies to reveal new perspectives on present times. These new points of view from South American media artists present a wide range of challenges to the ‘straightforward’ paths into the globalized world.

Brazil’s and Peru’s particular modernisms are marked by various parallels in their extravagant and creative precariousness, in the mass technological improvisation and complex temporal layers of their chaotic, violent and brutal cities, in their histories and memories.

Lima, the capital of Peru, represents a new paradigm of modernity that is, however, marked by paradox: chaos, poverty, mass access to technology, pirated technological products, historical buildings recycled into modern ones. All the signs of Peru’s socio-economic complexity are concentrated in this situation. São Paulo is Brazil’s financial and business centre, a place where extreme situations of poverty and wealth co-exist. What the two cities seem to have in common, and which is reflected in many works in this exhibition, is the coexistence of paradoxical situations in which the forces of modernity and precariousness are constantly at play.

On Dissemination /Julie Bélisle

Without constraint, there is sometimes great risk of being set adrift. In any event the existence of constraint quite often proves to be a powerful stimulant for the imagination. In the face of the teeming diversity of artistic practices in Brazil and Peru, we wanted to sketch a picture of media art in these countries. Constraint enters into play, first of all, in the use of new technologies, and then in restricting ourselves to the young generation of artists we wish to highlight. A generation, it quickly seemed to me, that is anti-Romantic, technological, chaotic in its organisation and at the same time socially committed in its art. These artists’ work is little seen in North America. The constraint, therefore, was not so much to look at work that reveals a coercive production context or whose subject matter is, necessarily, that of oppression—although this does appear in some of the work we have chosen—but rather to bring together work which makes apparent a multiplicity of constraints, from technological challenges to blocked memories, from social control to urban paranoia.

It must be said that the cities of São Paulo and Lima, with their dizzying numbers, both have effervescent artistic scenes. The former is sustained by its financial sector and by a significant network of museums, one-off events and commercial galleries,1 while the latter draws its support from individual and collective initiatives and from the private galleries and institutional structures that have arisen since the late 1990s.2 São Paulo, whose population density rivals that of Mexico City, has an international-calibre artistic scene, unquestionably the largest in South America. Brazilian artists, however, remain dependent on the support of private galleries; although collective structures emerge occasionally, it seems to me that there is less solidarity in the artistic community than there is in Lima. There the artistic scene, which has grown gradually, remains fragile on the level of its structure of events and is dependent on the will of the government of the day. Another thing that weighs heavily on the Peruvians is the country’s pre-Columbian past. The exotic image of the Incas persists in Peru,3 a country whose contemporary culture is of much less interest to locals and tourists. This, nevertheless, has the effect of generating artistic resistance, which manifests itself in the exploration of new technologies. The choice of non-traditional media4 acts as a sign of self-assertion.

These facts, offered here as a glimpse of the situation, are quite partial and incomplete, but they unquestionably modulate artistic production in each case. It is interesting to note also that the topic of globalisation frequently recurs in each country in the discourse of artists and critics alike, attesting to the emergence of a “common culture”. No culture shock thus awaits us when approaching Brazilian and Peruvian media art, something that may be due to the sharing of references brought about by the availability of the Internet, cable television and computers pretty much everywhere on the planet. While some people see globalisation as a threat, one that carries the risk of erasing our differences, a shared planetary culture could instead be synonymous with an opening up, in which each of us unavoidably contributes our own specificity.

The connections among the works chosen for Contrainte/Restraint are many and indicative of a plurality of practices. Although political commitment was associated with Latin American art throughout the twentieth century, this is not the dominant element of the work selected here. The themes of surveillance and violence are more often explored as a way of addressing the paranoia and danger that mark the reality of urban life. Beyond social concerns, however, today the city is a subject of fascination in itself; given its dimensions it becomes a space that cannot be taken in by the naked eye. This is the perspective from which Nicole Franchy models it, using various electronic circuits to construct a veritable network-city, none of whose zones communicates with the others. Rodrigo Matheus’ videos, meanwhile, grasp urban space through the use of digital technology. His abstract aerial views, assemblages of Google Earth satellite photographs, play upon the effects of distance, juxtaposition and scanning. Surprisingly, these two works do not take the South American continent as their subject, but rather even faster-growing cities in Asia. Juxtaposed with these images of sprawling cities are landscapes untouched by any human civilisation, the South Pole and the Grand Canyon, which act as a counterweight.

Gabriel Acevedo Velarde’s work Parálisis re-introduces us to urban architecture. Using animation, it transposes the neurotic anxiety of the city’s inhabitants onto its vegetation, turning weeping fig trees, the typical shrubbery of Mexico City and Lima, into characters of his video. His trees come to life in the midst of the city’s concrete spaces, shaking their leaves and yelling at passers-by—the effect of the urban fabric also being that of constraining nature. José Carlos Martinat, in his installation Stereo Realidad Environments 3: Brutalismo, reproduces the authoritarian architecture of the Peruvian Defence Ministry, commonly known as the “Pentagonito”. In his structure, Martinat installed printers connected to software that carries out search sequences on the Internet to find episodes in recent Peruvian history marked by the brutality of its battle against terrorism. The accumulation of printed textual collages gives material form to the extent of repression in Peru. The country’s history is also taken up by Rolando Sánchez, who recounts the horror of episodes in the terrorist guerrilla war or the 1980s by placing it at the heart of video games he designs, which are modelled on games from that time. His work Matari 69200—this figure being the number of deaths brought about by the conflict—recounts an episode in his childhood, when the arrival of colour television and the Atari 2600 video game console was accompanied by the dissemination of extremely violent images.

The video game aesthetic is also revisited by the duo Leandro Lima and Gisela Motta. In Armas. Obj. they pirate various games for their firearms. The resulting three-dimensional reproductions problematise our familiarity with images of violence, inserted here and there in playful situations. And we mustn’t forget their piece Alvo in the same series, an interactive target with the viewer in its line of sight.

Several works in the exhibition thus make use of virtual images to create the “visual” out of video games, modelling, Google Earth, algorithms or animation software. Nevertheless, the work of Amilcar Packer and Lucas Bambozzi brings us back to the brute reality of things and, to a certain extent, to the physical laws governing it. Here the image is not obtained through transposition but following the experience of performative protocol and the programming of innocuous gestures. With Video #15, Packer puts a truck to use in new ways, turning it into the site of a performance. Naked and seated in the middle of the box while the vehicle is moving, Packer tries to bring the jolts which inevitably make him fall and lose his position under control. The two cameras capture an activity in which the danger resides in the physical risk to which he subjects his own body. Bambozzi’s Run>Routine, meanwhile, is an installation that encodes the fall of various objects into a program that orders them by chance. The work thus takes the form of a repetitive interface that creates a dialogue between various individual scenes and whose fragments, while constrained by a program, remain unpredictable and chaotic. The language of computers thus becomes a tool for controlling and formatting incidents of domestic routine.

*

In the end, growth in the movement of goods and the flow of information gives rise, as we can see, to a feeling of complicity which manifests itself beyond borders. And it may be an essential aspect of the new media scene to promote the birth of new communities and new modes of expression in settings where technology proliferates. The experimentation associated with media art thus promotes exchange, regrouping and dissemination of artistic endeavours, both on the Internet and via countless events around the world. It is as if the arrival of these technological “artefacts”5 contributed to dismantling borders.

Julie Bélisle

August 2009

- Agnaldo Farias and Moacir dos Anjos, The Turn Generation 10 + 1: Brazilian Art in Recent Years (São Paulo: Instituto Tomie Ohtake, 2007), 28-68.

- Mauricio Delfín and Miguel Zegarra, “Electronic Art in Peru: The Discovery of an Invisible Territory in the Country of the Incas”, Third Text, vol. 23, no. 3 (May 2009): 293-301.

- Ibid., 293.

- Ibid. See also the article by José-Carlos Mariátegui, “Peruvian Video/Electronic Art”, Leonardo, vol. 35, no. 4 (August 2002): 355-63.

- A term used by José-Carlos Mariátegui in his article “Emergentes: Process-Based Works”, Emergentes (Gijón, Spain: LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial, 2007), 30-38.

The Technological Life of the Savages – São Paulo: Topography of Exclusion (1) /

Kiki Mazzucchelli

With a population of over 10 million inhabitants and a chaotic urban fabric formed by clusters of high-rises and sprawling slums, São Paulo is perhaps the Brazilian city in which the contradictions at heart of the country’s society are most pronounced. It is Brazil’s financial and industrial centre and the largest middle class consumer market in Latin America, producing 40% of the country’s GBP in a city where approximately one million inhabitants still live below the poverty line. This acute economic and social gap is the expression of specific forms of sociability prompted largely by private interests which, in their turn, have produced the deregulated forms of expansion and development that characterize São Paulo’s contemporary cityscape.

In fact, the city’s last and only major state intervention in urban planning was Francisco Prestes Maia’s master plan, and even this was only partially carried out during the 1930s/40s. The plan proposed opening a series of large avenues connecting the centre and the outskirts, privileging automobile circulation over public transportation. It required a great amount of demolition and remodeling of central areas, stimulating real state speculation and driving out the working classes, who could no longer afford the increased rents. This contributed to the production of a physical translation of an extremely imbalanced economic and class system by establishing the centre-periphery model of urban segregation(2), where basic infrastructure and public services (paving, lighting, sewage, hospitals, schools, etc.) are predominantly concentrated in central areas; a model which prevailed until the end of the 1970s.

From the 1980s onwards, this model of segregation by distance would start to gradually change, as an upper class population began to migrate into the newly built fortified enclaves located on the outskirts of São Paulo, bringing together rich and poor into the same geographical areas for the first time. At the same period, crime rates in the city—including robberies, thefts, kidnappings and violent deaths—began to rise, and safety (or rather the lack thereof) became a major factor in the shaping of the cityscape. The São Paulo topography we witness today, with its ubiquitous walls, electric fences, CCTV cameras, private armed security guards, double-gated garages and bulletproof cars is the product of a historical movement of retreat of the middle and upper classes from public spaces—and consequently from public life—and their embracing of a lifestyle the core values of which are security and private, personalized facilities and services.

The Age of Control and Surveillance

At present we have a situation in which public spaces in general are largely neglected both by the state and by middle and upper class citizens at the same time as private spaces become increasingly controlled; with the security industry’s degree of creativity often reaching comic proportions, such as in the widely popular apartment building gates featuring a rectangular slot where the anonymous and—following the elite’s logic—potentially delinquent food delivery workers can hand over pizzas without having to enter the property. In the current scenario, according to social scientist Teresa Caldeira, inequality has become an organizing value. Caldeira maintains that the current model of fortified enclaves creates “a space that directly contradicts the ideals of openness, heterogeneity, accessibility, and equality that helped to organize both the modern type of public space and modern democracies,” thus also transforming the way in which public spaces are perceived and used, “constituting the public as left-over space.”(3) Consequently, the working and social lives of the elites are increasingly led behind closed doors.

It is in this extremely fearful, markedly divided and highly monitored context that the works of the São Paulo artists included in this exhibition emerge. The themes of control and surveillance are foregrounded both in the series of three videos created by Rodrigo Matheus, in which he uses images from Google Earth, and in the interactive installation by Leandro Lima and Gisela Motta, in which a projected firearm scope follows visitors as they move about the exhibition space. Each of Matheus’ video pieces focuses on a different part of the globe, bringing to light distinct aspects of the program’s functionality and scope and problematizing this modern type of surveillance technology and its connection with military and corporate control through the creation of obscure, cinematic, suspense-ridden scenarios. Lima and Motta’s work deals more specifically with the paranoid feelings experienced by São Paulo citizens on a daily basis, which are possibly as much the product of real crime as of the ostentatiously aggressive security measures found in private spaces.

2006: We are all in Hell

In 2006 São Paulo experienced the greatest public security crisis in its history. The penitentiary system was shaken by rebellions, public and private buildings such as police stations, courts, bank branches and supermarkets were the target of bombs, grenades and shootings. Over two hundred buses were set on fire. Several policemen and penitentiary staff were killed. These attacks—which employed terrorist tactics—were orchestrated by a criminal organization known as the PCC (First Command of the Capital) which was formed in São Paulo state prisons in 1993, and took place in three week-long episodes in the months of May, July and August, just before the governmental elections in October. From within prisons across the state of São Paulo, the PCC leaders used smuggled mobile phones to coordinate these actions, which started as a reaction against the transfer of several PCC inmates to high-security penitentiaries.

This unprecedented upheaval sparked intense media coverage, and fear spread to other Brazilian states where no attacks had taken place.(4) In the midst of the crisis, journalist and filmmaker Arnaldo Jabor published a fictional interview(5) with Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho, a.k.a. Marcola, the main leader of the PCC. In the following months the text, in which the interviewee comes across as a very articulate critic of the inequalities of Brazilian society, making references to Dante and Hélio Oiticica, was widely circulated through emails and blogs, and often taken as a real interview.

Commenting on the emergence of a new class of citizens who choose organized crime as a way to escape absolute poverty and invisibility, the fictional Marcola stated that “post-misery generates a new murdering culture, aided by technology, satellites, mobile phones, the internet, modern weapons.” With “Chinese products” now available in an unprecedented way, modern surveillance technologies and global communications were quickly embraced by a new generation of criminals. For a while, the city seemed to be in the hands of the PCC. Under the circumstances, “Marcola’s” last sentences seemed to synthesize the feelings of apprehension of São Paulo’s inhabitants at the time: “Leave all hope behind. We are all in hell.”

Division as Norm

In a way, Jabor’s story had the merit of giving massive visibility to the issue of daily violence committed against the poorer sections of São Paulo society, a subject that is largely ignored by the media due to its sheer banality.(6) The naked body presented by Amilcar Packer in his immersive video installation seems to evoke the bodies of those people who are left on the other side of the elite’s fences and walls, bodies deprived of basic human rights and excluded from the judicial order instituted by sovereign power. Packer’s body is presented in an enclosed dark space, subjected to external forces that throw it about violently as it tries to stabilize itself on a chair, highlighting both its vulnerability and resoluteness.

Lucas Bambozzi’s installation Run>Routine, on the other hand, proposes a more sarcastic approach towards the posture of self-centeredness assumed by a large section of the middle and upper classes in São Paulo. In this piece, Bambozzi associates several computer routines with domestic routines, pointing to the naïve and selfish belief that daily life could be completely controlled, programmed and free from the chaos represented by the public left-over space and its inhabitants.

Technology is the Answer, but What is the Question?(7)

São Paulo has always had a cosmopolitan vocation, and today it is more global than ever. However, its current levels of wealth concentration are shameful and security is used as an excuse to enforce exclusionary practices that guarantee the elite’s social exclusivity. In this context, technology appears mainly as an instrument of control and surveillance, especially of private spaces. Curiously, it is very rare to find any type of social or political analysis of technological art in Brazil—a field which has rapidly expanded in the 2000s and which is, by national standards, generously funded.

Mirroring the topography of the city, several technology festivals and exhibitions are sponsored by the private sector and are primarily used as semi-free marketing tools(8) for major multinational companies. Surely, many people in the wider field of Brazilian culture have been developing extremely interesting projects—such as in the case of open source technology—but the new media sector still privileges the spectacular, blockbuster aesthetics over critical content. Paulistanos still aspire to a position of synchronicity in relation to the hegemonic cultures that they attempt to emulate, but as long as exclusivity and security, motivated by private interests, are the core values of this society, this will remain a distant dream.

Kiki Mazzucchelli

- The title of this essay was borrowed from the Brazilian post-punk compilation “The Sexual Life of the Savages”, organised by the artist duo Tetine and released in 2005 by the British label Soul Jazz which, on its turn, was borrowed from the homonymous book by Malinowski from 1929.

- For an in-depth study on the relationship of fear, crime, segregation and urban development in São Paulo see City of walls: crime, segregation, and citizenship in São Paulo, Teresa Caldeira, pp.220-221. London: University of California Press, 2000.

- See Teresa Caldeira, “A contested public: Walls, graffiti, and pichações in São Paulo, inLagnado, Lisette and Pedrosa, Adriano (ed). 27a. Bienal de São Paulo: Como Viver Junto. São Paulo, Fundação Bienal, 2006.

- A survey commissioned by the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo and IBOPE, published on 29/08/2006, showed that 26% of the São Paulo population altered their daily routines because of the PPC attacks. Curiously, similar percentages (19 to 28%) were repeated across all regions in Brazil, although the attacks occurred almost exclusively in the state of São Paulo.

- The interview was published in the newspaper O GLOBO on 23/05/2006.

- However, it is important to note that the text also suggests a direct link between poverty and criminality, a contentious subject which I am not going to develop here.

- Quote attributed to the architect Cedric Price.

- Under the current cultural incentive laws (Rouanet), the private sector can ‘invest’ in cultural projects of their choice, as long as these are approved by the government, although there is no clear cultural agenda. A percentage of the amounts invested is deducted from the company’s tax.

Historical Falterings & Urban Dystopia: Turning off, recording, transmitting, and lighting a city / Miguel Zegarra

According to the latest national census, 27.8% of Peru’s population is concentrated in Lima, with its 7,695,742 inhabitants in a 2,812 km2 area (0.2% of the Peruvian territory)(1). Due to an accelerated migration process and population overflow, the city has spread within a few decades by developing important growth centers(2). In the midst of this accelerated expansion, a chaos has taken shape in this national idiosyncrasy— arising from internal migrations driven by the violence of recent history—and configured this city as a synthesis of Peru: a model of civil society dissociated from the State(3) in which hybrid forms of development and modernity coexist.

This process has led to a radical transformation of the cityscape: environments of extreme poverty and wealth live side by side, historic buildings are recycled into makeshift buildings, and mass access to technology is provided by informal internet booths, pirated products and recycled electronics.

Recycling technologies and information is one of the defining characteristics of Peruvian media art. The various zones where technological recycling takes place in Lima make up a cyberpunk topography where self-styled electronic engineers sell robots by the side of mountains of electronic scrap. These “public laboratories” for materials and ideas are concentrated in the city’s downtown(4).

Blackout

It would be hard to imagine how electronic artworks could have functioned in 1980s Peru. The constant terrorist attacks on electricity pylons would have caused these works to turn on and off, before completely breaking down.

Between 1980 and 1990 the country experienced a process of internal war to which Lima turned its back. The first contact with violence was via the media, mainly through the written press and television. The conflict then took to the city, turning the streets into areas of violence and death. Matari 69200 by Rolando Sánchez, investigates the experience of public media in private space by referring to the imaginary and memory of a generation. The generation of artists gathered in Restraint lived a secluded life in private spaces delimited by screens (turned on, and then abruptly turned off by the explosions), which showed video games and cartoons interspersed with news segments about hyperinflation, epidemics, genocide and destruction(5).

Paranoia

The political regime of the 1990 decade began and ended on videotape. The period opened with the capture of Abimael Guzmán, the leader of the Shining Path terrorist group, and the dissemination of a video of him dancing Zorba the Greek with his top leadership. Another video closed the decade: the bribing of an elected congressman by the presidential advisor Vladimiro Montesinos, which was filmed by the Peruvian Intelligence department and then transmitted on television(6). The broadcasting of this event changed the course of history by revealing a web of political and media corruption.

Deborah Poole describes the control of a “thousand-eyed” State that is omnipresent and omniscient. In the early 1990s television images of both known and suspected terrorists wandering through Lima’s public spaces were frequently shown. These films were trying to bring home the idea that no individual walking along the streets could escape the eyes of the State. Through these type of reports the Fujimori regime sought to convey the idea that the State had not only an unlimited capacity for surveillance, but also an arbitrary control over what people could see or not see(7).

In Stereo Reality Environment 3: Brutalismo, José Carlos Martinat appropriates an architecture that is emblematic of surveillance and power(8). The artist generates new information by symbolically infiltrating the information control network of the Pentagonito (“little Pentagon” – the seat of the Army Intelligence Service and of the system of political corruption). The paranoia of control is reflected in the automatic launching of random information found in the network, and which falls printed into our hands.

As a consequence of this logic of state-directed surveillance and the conception of public space as a place of violence, the citizens of Lima live in a state of extreme fear and paranoia. Parks and squares are beginning to disappear in the city. Moreover, the privatization of public spaces according to upper class criteria has fostered a “ghetto and apartheid culture” cut off from a growing metropolis. Many streets are blocked by gates that protect houses, which have been converted into small bunkers watched over by unarmed guards. The “huachimán” (the hispanicized Peruvian form of “watchman”) guards the properties from a precarious makeshift booth on the sidewalk. It is in this way that urban development patterns, which promote attitudes of withdrawal and distrust, have emerged.

Like the “huachimanes,” the bushes in Gabriel Acevedo’s video Parálisis have their trunks locked in by cement, yet they move about and catch our attention, letting us know that they are watching over us from their confined space. The shaking of these shrubs—controlled from the root to the crown—seems to replicate the citizens’ psychological state: their feelings of paranoia and held back violence.

Lighting the City

Whereas the 1980s and 1990s were marked by the erasure of public space due to violence and control policies, the 2000s gave rise to new public spaces in consumer centers and in media experiences. Department stores, screens and the internet have come to define new social attitudes. The new squares are the shopping malls; highways and chat rooms are the new traffic sites.

Consequently, the experience of screens, which define current media art practices, generates escape routes while also positioning one before a faltering reality, perceived more than ever as a mediated simulacrum. New media art appropriates the interfaces of power by transforming them and calling for a new public space of versatile platforms open to experience.

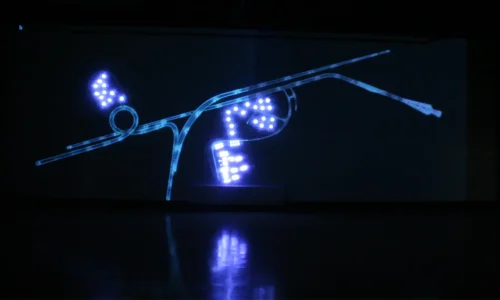

With Satellite Cities Nicole Franchy illustrates a new city of screens and information traffic flows. The city is viewed as a big screen of electronic circuit boards leading towards a standardized and dystopian horizon. Although the installation’s interrupted dynamic refers back to mediated experience as isolation, it also offers us a panorama we are free to control: we can re-appropriate the lost territory.

***

The control of the media and information traverse Peruvian history intermittently. Political powers’ manipulation of reality through media platforms, the on/off electrical power supply due to terrorist bombs, and the video surveillance transmitted to State intelligence systems have constantly served as strategies to control and restrict public space(9). The large-scale information access platforms, in combination with the reworking of the dissemination of media recordings through art, have opened paths towards new points of convergence for communities and imaginaries, and indicated new potential ways of exercising power.

Miguel Zegarra

- INEI – Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (National Statistics and Data Processing Institute). August, 2008.

- Three large urban cones—North, East and South—have overcome the disastrous impact of a decade and a half of violence, becoming main bastions of economic development thanks to a substantial use of information and communication technologies in their social relations. José Matos Mar. Desborde Popular y crisis del Estado. Veinte años después, Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso, 2004.

- Ibid. p.148.

- It is worth highlighting recent institutional developments in this area, such as Escuelab (http://www.escuelab.org/), an educational and experimental creation laboratory.

- The event that radically changed the relationship of middle class Lima citizens to violence was a 1992 car bomb explosion in the residential zone of Tarata street, in the Miraflores neighbourhood.”What it changed was the relationship of everyone with terrorism: from having been randomly in target range, to being the primary target.” Max Hernández Calvo and Jorge Villacorta. Franquicias Imaginarias. Las opciones estéticas en las artes plásticas en el Perú de fin de siglo, Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Peru, 2002. p. 98.

- The 90s was also a flourishing period for Peruvian video art production, a practice which is losing ground nowadays, since it is being displaced by more sophisticated media proposals.

- Deborah Poole. Videos, corrupción y ocaso del Fujimorismo, Lima: Instituto de Defensa Legal, 2008.

- During the years of military rule (1968-1979) an official style designated the architecture: “brutalism.” Its aesthetic was functional and linked to modernism, and it took visible form in the construction of public buildings. Post-Ilusiones/Nuevas Visiones:Arte Crítico en Lima (1980-2006), Lima: Fundación Augusto N. Wiese, 2006. p. 25

- Referring to Alberto Fujimori’s dictatorial government’s mass media control network, Rodrigo Quijano distinguishes between a repression of all forms of expression not subject to manipulation, and a planned media structure to extort and bribe newspapers and television channels. Puntos Cardinales 2001. 4 artistas visuales peruanos, Lima: Quidam, 2002.

Julie Bélisle

Julie Bélisle holds an MA in museology and has been working at the Galerie de l’UQAM since 2004. For her current doctoral studies in art history at UQAM she is focusing on accumulation processes in contemporary art, a specialization which has led her to participate in several anthropology research projects. She has published texts in various journals and exhibition catalogues and in 2007-2008 she took part in a writing residency at the 3e impérial (Granby, Québec). She also co-curated the exhibition Basculer presented at the Galerie de l’UQAM in 2007, conceived i, a virtual exhibition that gathered 32 Canadian artists, and curated an exhibition on the work of the artist Monique Régimbald-Zeiber which was presented in Europe in 2008.

Kiki Mazzucchelli

Kiki Mazzucchelli is an independent curator and writer working between London and São Paulo. In 2009, she curated Jonathas de Andrade’s solo exhibition Tropical Hangover (Galeria Marcantonio Vilaça, Recife) and an exhibition-in-print project for the magazine Carnation (São Paulo). In the same year she was awarded a two-month International Curator residency from the Fundación Gilberto Alzate Avendaño (Bogotá, Colombia). Recent curatorial projects include the group show Looks Conceptual or How I Mistook a Carl Andre for a Pile of Bricks (Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo), Brazilian photographer Barbara Wagner’s solo show Brasília Teimosa (ICA, London) and the sound-based exhibition OIDARADIO (Paço das Artes, São Paulo). Her writings feature in several publications such as Bravo!, Cultura & Pensamento, ArtPress, Flash Art and others, as well as in various exhibition catalogues. She is the UK correspondent for the Spanish magazine ArteContexto, member of the CCSP group of external curators and served as a jury member for the Technology Connections Festival promoted by Instituto Sergio Motta (São Paulo, June-July 2008).

Miguel Zegarra

Miguel Zegarra was born in Lima, 1979. He graduated in History from Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Since 2007, he is the curator of Galería Vértice in Lima. From 2004 to 2006, he was co-curator of the traveling international exhibition, Vía Satélite. Panorama of photography and video in contemporary Peru presented in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Montevideo, Santiago, San José and Lima. Since 2004, he has been curator of the International Festival of Video and Electronic Art in Lima (VAE). He has also curated the video installation by the artist Patricia Bueno that represented Peru at the 52nd Venice Biennale (2007). His recent curatorial projects include La generación del espectáculo: Arte peruano contemporáneo (Galería Kiosko, Bolivia, 2009), En tránsito al paraíso: Imaginarios de la migración (Galería Vértice, 2009), La construcción del lugar común (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Lima, 2008), Zona de desplazamientos: Videoarte peruano contemporáneo (MAMba Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2007). He has published texts in different magazines like Third Text (London), Contemporary (London), Arte Al Día International (Buenos Aires) and Artmotiv (Lima). Recently he was selected to be part of the Peruvian delegation for the X Bienal Internacional de Cuenca (Ecuador, 2009), as a member of a curatorial team.

Artists & works

Amilcar Packer

Vidéo #15

2008

Video installation

Description of the work

Since the beginning of his career, Amilcar Packer has been exploring the relationship between the body and its environment, testing its possibilities and limitations by creating temporary assemblages formed by his own body and clothes, furniture and architectural features of enclosed spaces. His seemingly absurd, studio-based Naumanesque experiments initially resulted in photo-performances; more recently he has produced photographic and video works that take place in urban space.

The two-channel video installation Video #15 records Packer’s unwavering attempts to keep seated on a chair in an enclosed space without windows or doors. This image is simultaneously presented in two different angles to the viewer, who stands between the symmetrically opposed screens as if trapped inside the same room. We can hear loud rumbling sounds as the room quakes vigorously and the artist’s body is violently thrown against the walls. It is only after a while that we realize that the action is taking place on the back of a moving truck.

In spite of not making any direct reference to these themes, the installation suggests a range of situations linked to biopolitical power: torture, forced displacement or the smuggling of immigrants across borders. Both the work and the images it evokes are exemplary of some circumstances where the body is subjected to external forces or external control. But at the same time as exposing the fragility of the body, Video #15 also emphasizes its resoluteness, as the artist is constantly returning to his initial position.

Biography

Amilcar Packer was born in Santiago de Chile, in 1974 and lives and works in São Paulo. In 1999, he graduated in Philosophy from the Universidade de São Paulo. He studied with Eduardo Brandão from 1998 to 2001 at the independent art school Terceiro Andar. His recent solo exhibitions include Entre, Usina do Gasômetro, Porto Alegre, Brazil (2009), Polisemiose at the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, São Paulo (2006) and Grave at Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo (2005). His work was featured in many recent group shows such as the 2nd Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki, Greece (2009), ‘Tipos móviles’ in the 2nd Trienal Poligráfica de San Juan, San Juan, Porto Rico (2009), ‘Farewell to Post-Colonialism’ Third Guangzhou Triennial, Time Museum/Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China (2009) Interrogating Systems, CIFO Grants and Commissions Exhibition, Miami (2008), Geração da Virada, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo (2006), Con los Ojos del Otro, Centro Cultural de España, Montevideo (2006) and the Sydney Biennale (2004).

Gabriel Acevedo Velarde

Parálisis (Paralysie)

2005

Video, 2 min 15 s

Description of the work

In this video animation, nature is not immune to the neuroses of large city dwellers who live in places such as Mexico City where the artist made this piece. On the pavement stressed out shrubs scream, shudder, and moan to passers-by, as if absorbing their anxieties and undisguised sadness. The video shows a particular tree species, a bush/shrub, plentiful in cities such as Lima and Mexico City, the “Benjamin Ficus”. This simultaneously common and weird natural urban element represents contemporary cities’ restraint and control paranoia which extends even against nature, for these plants are always kept within concrete or asphalt borders and pruned in different ways and forms bordering on a kitsch obsession. The unexpected movement of these elements reveal themselves as a sign of a small revolution in everyday life.

Biography

Gabriel Acevedo Velarde was born in Lima, in 1976. He graduated in Fine Arts from Universidad de las Américas, Puebla, México. The artist studied film production and photography. His recent solo exhibitions include Quorum Power at Museo Carrillo Gil, Mexico City (2009), No matter what happens to you, we will keep growing at Y Gallery, Queens, New York (2008), Incorporación, desprendimiento at Galeria OMR, Mexico City (2008), Marathon at Galeria Leme, Sao Paulo (2008), Sinapsis Insurrección at Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, Mexico City (2006). His recent group shows include MALI Contemporáneo at Museo de Arte de Lima (2009), Guangzhou Triennial at Guangdong Museum of Art, China (2008), I/Legítimo at Paço das Artes / Museu da Imagem e do Som, São Paulo (2008), The Culture Clash, Working Rooms Project Space, London (2008), Fuck you human at Maribel Lopez Gallery, Berlin (2008), Zoótropo at Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City (2008), Panorama 2007 at Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, FACE-UP at Galerie Adler, New York (2007), Geopolíticas de la Animación at Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Sevilla (2007), En Perfecto Desorden at Museo de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (2007), The Fourth Seoul International Media Arts Biennale (2006), Contemporary Video Art from Brazil at Galerie Adler, Frankfurt (2006). He has received many awards from Fundación Jumex (2007), Rockefeller Foundation (2006), American Center Foundation (2007) and at the 15th Festival Videobrasil (Honorific Mention). The artist is represented by Galeria Leme in São Paulo. He lives and works in Berlin.

José Carlos Martinat

Stereo Reality Environment 3 : Brutalismo

2007

Interactive installation

Description of the work

Stereo Reality Environment 3: Brutalismo inhabits a space between physical and social architectures and archetypes. The artist’s model is a rendition of the iconic Peruvian “Pentagonito” which houses the Peruvian secret service. Its name was inspired by the Pentagon, the famous American Department of Defense building. The mechanized model serves as a cocoon for images and texts it spouts out. The association between “brutalisms,” brings forth dualistic associations spun from the dark history of the Pentagonito, juxtaposed with the allure of a brutal form.

Collection of Tate Modern

Biography

José Carlos Martinat was born in Lima, in 1974. He graduated from the Instituto Antonio Gaudí – Centro de la Fotografía. He studied sound design and interactive software and art. His recent group exhibitions include 7 Bienal do Mercosul (2009), 2nd Trienal Poli/Gráfica from San Juan (2009), MALI Contemporáneo at Museo de Arte de Lima (2009), Emergentes presented at LABoral in Gijón, Spain (2008) and at Fundación Telefónica in Buenos Aires, Santiago and Lima (2008-2009), 10°00 S / 76°00 W at Galeria Leme in São Paulo (2007), Doppelgänger: El doble de la Realidad at MARCO Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Vigo, Spain (2007), VAE9 Festival Internacional de Video/Arte /Electrónico in Lima (2005), World Wide Video Festival in Amsterdam (2004), Vía Satélite. Panorama de la fotografía y video arte contemporáneo del Perú, latinoamerican itinerancy. He received the Incentive for New Productions Award in the Vida 7.0 Arte y Vida Artificial Competition Fundación Telefónica, Madrid, Spain (2004). The artist is represented by Galeria Leme in São Paulo and Revolver Galería in Lima. He lives and works in Lima.

Leandro Lima – Gisela Motta

Armas.Obj. (Armes.Obj.)

2008

Paper objects, variable dimensions

Description of the work

The pistols, submachine guns, rifles and sniper guns reconstructed in paper by Motta and Lima were taken from several popular video games commonly known as shooters, a fairly wide subgenre of action games in which the avatars use some kind of weapon. In their turn, the guns featured in these games are digital renderings of actual popular firearms, most of which can be associated with a specific conflict or country. As well as making fairly accurate replicas, in-game weapons designers usually attempt to emulate the functioning of real guns to create a more realistic experience.

Motta and Lima have hacked the games in order to extract the original 3D files, which were then transformed into 2D files that were subsequently printed and assembled as life-size paper models. Arranged on the gallery wall in the style of a traditional gun collection, from a distance these pieces resemble real weapons, as their three-dimensionality gives them volume and ‘weight.’ But as visitors approach them, it becomes evident that these are only reproductions, as the polygonal simplification and the pixellated quality of the game files have been maintained.

This series addresses the complex issue of how perception is affected by technology, raising the question of whether virtual experience is any less real than what is experienced in the ‘real world.’ The link between exposure to video game violence and aggressive behaviour is a contentious subject that has been widely debated over the last decade. Brought back into the physical world, these weapons seem to regain— albeit temporarily—the gravity they have in the real world.

Biography

Leandro Lima and Gisela Motta were both born in São Paulo, in 1976. Between 1996 and 1999, they studied Visual Arts at FAAP in São Paulo, and since then they have been working in partnership. Their solo exhibitions include Sob Controle (2009) and Vivendo at Galeria Vermelho in São Paulo (2006) and Foreign Element at HIAP, Helsinki (2007). Their recent group exhibitions include the 10th Havana Biennale, Havana (2009), We Used to Be Painters at Plan 9, Bristol (2008), I/Legítimo at MIS, São Paulo (2008) and Aktuelle Videokunst aus Brasilien at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin (2007). Motta and Lima were artists-in-residence in the UK for a three-month period in 2008 through the Artist Links/ British Council program. In 2006, they were awarded the prestigious Marcantonio Vilaça Prize and they also won the Incentive bursary at the Sergio Motta Art & Technology Awards in 2004.

Leandro Lima – Gisela Motta

Alvo (Cible)

2008

Interactive installation

Description of the work

As visitors enter a determined field within the exhibition space, the image of a target is projected on their bodies, following them as they move about. Their image is captured in real time by a camera connected to a computer with software that receives a signal and decodes this image through a process called ‘tracking,’ which reveals a series of coordinates. This information is then used to automatically place the target on the visitor’s body. Only one target is projected, and it follows the visitor who moves the most. If nothing moves within the determined field, then the computer doesn’t identify any reference points in order to project the target, and the space remains empty.

This installation gives visibility to the state of constant paranoia experienced by many São Paulo citizens who feel not only that they are the potential victims of urban violence, but who are also increasingly monitored by pervasive security devices such as CCTV cameras, sensor-triggered alarms, and even heavily armed private security personnel. As such, it exposes the fine line that separates notions of aggression and protection, reminding us that the over monitored spaces and situations produced by excessive security measures can be as threatening and intimidating as those produced by crime. Following the logic of the panopticon, this interactive installation also evokes a paranoid feeling that emerges from modern surveillance technologies’ ability to exercise the ‘power of mind over mind.

Biography

Leandro Lima and Gisela Motta were both born in São Paulo, in 1976. Between 1996 and 1999, they studied Visual Arts at FAAP in São Paulo, and since then they have been working in partnership. Their solo exhibitions include Sob Controle (2009) and Vivendo at Galeria Vermelho in São Paulo (2006) and Foreign Element at HIAP, Helsinki (2007). Their recent group exhibitions include the 10th Havana Biennale, Havana (2009), We Used to Be Painters at Plan 9, Bristol (2008), I/Legítimo at MIS, São Paulo (2008) and Aktuelle Videokunst aus Brasilien at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin (2007). Motta and Lima were artists-in-residence in the UK for a three-month period in 2008 through the Artist Links/ British Council program. In 2006, they were awarded the prestigious Marcantonio Vilaça Prize and they also won the Incentive bursary at the Sergio Motta Art & Technology Awards in 2004.

Lucas Bambozzi

Run>Routine

2007

3 Channel computer-based video projections

Description of the work

Run>Routine was created from the observation of common operations that people carry out everyday and which are based on computer routines. For instance, the choice of a song or of a video file in a player in which there is a graphic interface, a repetitive process which is foreign to the world we normally live in and listen to.

The title is important: ‘run,’ in computing language, is a kind of habit associated to the execution of commands, scripts, programs or programming routines. That is, it is a command that triggers events. The word ‘routine’ affirms the ironic character of the project, as it suggests something less than a habit and more like a repetition of small everyday life incidents.

Run>Routine seeks to associate coding routines with domestic routines. If the former are ‘programmable,’ supposedly unfailing, the latter are almost always unforeseeable. But both can cause tribulations.

The work consists of a synchronized system, with two screens, one of them running the programming script that randomly triggers the videos and another showing the short clips of the incidents—things falling, producing a repetition of small chaotic sequences that capture the viewers’ attention for an instant in a singular fashion.

(Text by Lucas Bambozzi)

Biography

Lucas Bambozzi is a multimedia artist based in São Paulo, Brazil. His works have been shown in solo and collective exhibitions in more than 40 countries. He was a visiting artist at the CAiiA-STAR Centre, where he has developed an extensive research about on-line privacy and pervasive systems, as part of his M.Phil. studies, concluded in 2006 at the University of Plymouth, UK. His research on media and art has led to a series of curatorial projects such as: Life Goes Mobile (2005) and arte.mov, International Mobile Media Art Festival (2006-2009). Bambozzi has been working with collectives FAQ/feitoamãos and Cobaia, dealing with live video performances and media intervention projects in public spaces. His recent exhibitions include Interconnect at ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany (2006), Pensée Sauvage – on Freedom at Frankfurter Kunstverein in Germany (2007) and Emergentes at LABoral, (2007/2008) Gijon, Spain and RE:akt!, at ŠKUC gallery, Ljubljana in Slovenia (2009). He is represented by Luciana Brito Galeria in São Paulo.

Nicole Franchy

Satellite Cities

2009

Interactive installation

Description of the work

Nicole Franchy’s research began with the study of the accelerated growth of Chinese cities in the Pearl River delta. This huge urban area, a meshwork of architecture and landscape covering 1500 kilometres of highway, connects three cities, and has 5 airports. This great parasite organism—apparently perfect—encompasses dysfunctions due to its vertiginous growth: ghost towns that are disconnected from the networks of abandoned highways and industrial complexes. Following this discussion, Franchy provides an analogy between electronic circuit patterns and these new models of urban growth. This is an interactive installation based on a dystopian view of contemporary global society as well as on the technical specifications of a circuit: a technological nomenclature. Franchy abstracts architectural constants and standardizes them in three patterns that structure the models of three cities. The installation configures a translucent network similar to that of a living organism in which one can see the functioning of its internal organs. This seemingly perfect system encloses functionality in a paradoxical form: the video projections of highways in the midst of the transparent diorama do not connect the different zones with each other but, on the contrary, isolate them.

Biography

Nicole Franchy was born in Lima, in 1977. She graduated from Escuela Superior de Bellas Artes Corriente Alterna (Silver Medal, Honours). She studied interactive software at Centro Fundación Telefónica in Lima and she is starting a Master Degree in Fine Arts at HISK Higher Institute for Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium. Her recent solo exhibitions include Patron 3.15 H9 at Galería Vértice, Lima (2008), Espacios Compartidos at Centro Cultural Ricardo Palma, Lima (2006) and Urbania at Galería 5006, Buenos Aires (2007). She participated in recent group shows such as Des-habitables (traveling exhibition: Lima, Madrid, 2009-2010), La construcción del lugar común at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Lima (2008), Frontera / under the skyline at Galería Vértice (2007), Buenos Aires Photo at Palais de Glace, Buenos Aires (2006 and 2007 editions), Método de Duda at Galería Artco, Lima (2003). She has received many awards such as the First Prize of Photography Humboldt / Goethe Institute, Lima (2002) and she was a finalist for the X Concurso de Artes Visuales “Pasaporte para un Artista” / Embajada de Francia, Lima (2007) and the Unión Latina Prize (2008, finalist). She lives and works between Rome and Belgium.

Rodrigo Matheus

Grand Canyon

2008

Video, 4 min 12 s

Description of the work

While both South Pole and Tokyo consist of zooming effects and long takes, Grand Canyon revolves around several takes captured at various speeds and angles that were later edited together. This time the camera travels mainly across the canyon’s uninhabited land and the soundtrack evokes a sense of nervousness and suspense.

As the camera moves, a range of visual effects takes place: mountains are formed, pop up and disappear, as if the land was alive and pulsating. These effects actually result from a combination of connection speed and navigation controls, which affect the speed of the camera movement and image rendering.

The Grand Canyon is one of the few places in Google Earth with 3D elevation views, and it is also amongst its most popular destinations.

Biography

Rodrigo Matheus was born in 1974, in São Paulo. He completed a B.A. in multimedia at the Faculty of Arts and Communication of the University of São Paulo. He has exhibited extensively in Brazil and abroad. In 2008, he had a solo exhibition at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo and took part in several group shows including Looks Conceptual or How I Mistook a Carl Andre for a Pile of Bricks at Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo, and Images Festival at Art Gallery of York University, Toronto. Other recent group exhibitions include Arquivo Geral at Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro (2006) MAM na Oca at Oca, São Paulo (2006) and Paradoxos Brasil – Rumos Artes Visuais at Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Centro Dragão do Mar Arte e Cultura, Fortaleza, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiânia and at Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro (2005/2006). The artist is represented by Galeria Fortes Vilaça in São Paulo.

Rodrigo Matheus

South Pole

2008

Video, 3 min 3 s

Description of the work

South Pole s’ouvre sur des images abstraites et des formes géométriques qui se transforment lentement et ressemblent parfois à un iris. Lumière et noirceur oscillent à l’écran, sur un fond musical qui évoque un certain mystère, jusqu’à ce qu’une vive lumière blanche finisse par dominer. Le rythme hypnotique et les images mystérieuses demeurent jusqu’aux trois quarts du film environ.

Puis la caméra amorce un recul et révèle les contours de cette masse blanche bordée de taches bleu vif. Ce n’est qu’à la toute fin, quand elle fait apparaître les contours de la planète, que nous comprenons enfin ce que nous venons de voir. Ce territoire glacé, désolé et largement inconnu, est représenté ici au centre du globe, ce qui le fait paraître plus proche, plus accessible.

Élément de la trilogie Google Earth de Rodrigo Matheus, cette vidéo révèle à quel point nos pulsions voyeuristes sont aiguillonnées à l’idée d’une technologie qui dévoile sur l’écran de notre ordinateur des lieux distants, auparavant inaccessibles. Suivant la logique du programme, nous concluons alors que la caméra a commencé par scruter de près le territoire réel pour nous montrer le pôle Sud tel qu’il est vraiment. Or, les satellites ne peuvent pas enregistrer les images de cette région du globe, qui est couverte de neige et qui, par conséquent, réfléchit la lumière blanche. Ce que l’artiste a mis sous nos yeux est un ensemble de formes et de couleurs mouvantes, qui frustre notre désir de voir ce qui n’a jamais été vu.

Biography

Rodrigo Matheus was born in 1974, in São Paulo. He completed a B.A. in multimedia at the Faculty of Arts and Communication of the University of São Paulo. He has exhibited extensively in Brazil and abroad. In 2008, he had a solo exhibition at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo and took part in several group shows including Looks Conceptual or How I Mistook a Carl Andre for a Pile of Bricks at Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo, and Images Festival at Art Gallery of York University, Toronto. Other recent group exhibitions include Arquivo Geral at Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro (2006) MAM na Oca at Oca, São Paulo (2006) and Paradoxos Brasil – Rumos Artes Visuais at Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Centro Dragão do Mar Arte e Cultura, Fortaleza, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiânia and at Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro (2005/2006). The artist is represented by Galeria Fortes Vilaça in São Paulo.

Rodrigo Matheus

Tokyo

2008

Video, 6 min 25 s

Description of the work

At the beginning all we see is a blurred image whose various elements are rather indistinct. But as the camera slowly zooms out, we can start identifying the grey solid blocks which appear to be floating over what we can now recognize as a kind of suburban scenario with the houses located in seemingly quiet streets. The lengthy camera movement is now accompanied by a cacophony of voices speaking in a foreign language—apparently Japanese.

A few seconds later, one enters what is familiar territory for most internet users; it now becomes clear that this is a Google Earth camera gradually revealing an aerial view of a city. Simultaneously, the soundtrack becomes increasingly more jarring, adding a certain sense of tension to this seemingly ordinary video. Soon, a few corporate logos start to pop up as if to denote locations that have been identified via satellite data.

But, as the camera continues to zoom out these logos start to rapidly proliferate, to the point when they almost entirely cover the depicted area. The sound slowly subsides and the logos start to vibrate madly and ridiculously in synchrony with a kind of pop techno track reminiscent of video game sounds.

Tokyo plays with the notion that the possibilities offered by recent surveillance techniques are undoubtedly seductive, as they potentially create windows to every part of the world at the click of a mouse. However, it equally reminds us that these same spaces also become much more vulnerable to the control and exploitation by corporate or military power.

Biography

Rodrigo Matheus was born in 1974, in São Paulo. He completed a B.A. in multimedia at the Faculty of Arts and Communication of the University of São Paulo. He has exhibited extensively in Brazil and abroad. In 2008, he had a solo exhibition at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo and took part in several group shows including Looks Conceptual or How I Mistook a Carl Andre for a Pile of Bricks at Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo, and Images Festival at Art Gallery of York University, Toronto. Other recent group exhibitions include Arquivo Geral at Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro (2006) MAM na Oca at Oca, São Paulo (2006) and Paradoxos Brasil – Rumos Artes Visuais at Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Centro Dragão do Mar Arte e Cultura, Fortaleza, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiânia and at Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro (2005/2006). The artist is represented by Galeria Fortes Vilaça in São Paulo.

Rolando Sánchez

Matari 69200

2005

Video games

Description of the work

The Matari 69200 project focuses on the political violence suffered during the 1980s in Peru. The medium used by the artist for this purpose is a video game and the ATARI 2600, a very popular video game console during the same decade. The number “69200” in the title refers to the number of fatalities during the war. The armed conflict was between the Peruvian government, represented by the Army, and the Maoist Shining Path guerrilla. Thousands of people were murdered and tortured and many others disappeared. The brutality came from a fundamentalist guerrilla and from the police force who carried out an abusive and indiscriminate repression that did not respect any human rights. The same TV screen that showed images of this war was also used for playing Pac Man and Space Invaders. Matari 69200 conflates these two experiences into a video game based on episodes of a real war.

Biography

Rolando Sánchez was born in Lima, in 1974. He graduated from Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes de Lima and from the Electronic Engineer Faculty of Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú where he is a regular teacher. His recent group exhibitions include Homo Ludens Ludens at LABoral, Gijón, Spain (2008), Videt 08 International Festival of Vilafranca del Penedés, Barcelona, Spain (2008), V Bienal iberoamericana de Videocreación y Arte Digital Inquieta Imagen at Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo de San José, Costa Rica (2007), 3rd Festival of Electronic Art, Rosario, Argentina (2006), VAE10 Festival Internacional de Video/Arte/Electrónica, Lima (2006), 2nd Festival of Electronic Art 404, Rosario (2005), Break 2.3 New Species, Ljubljana, Slovenia (2005), Artware 3 at Centro Cultural de la Universidad Católica, Lima (2005), Softmachine at Galería Artco, Lima (2005). Sánchez was awarded prizes at the “III Exhibition of Digital Art” (Video installation category, Santa Fe, Argentina, 2006) and the First Prize Metropolitan Contest for Young Visual Artists (Lima Municipality, 2006). He lives and works in Lima.