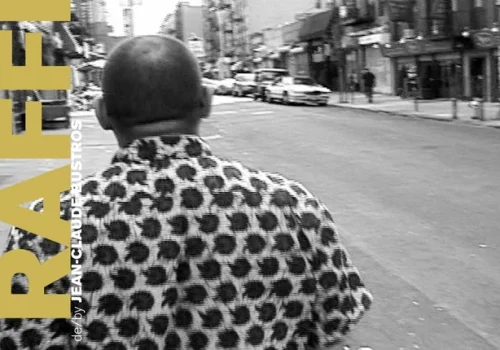

Raffi

Parisian Laundry, Montréal

From October 26th, 2006 to January 2nd, 2007

This first collaboration with Parisian Laundry gallery will present the new interactive installation of Jean-Claude Bustros, Raffi.

From 1999 to 2004 while making frequent visits to his New York apartment, Bustros documented Raffi on film and video format. The different portraits confronts the visitor to the many personas of Raffi. While navigating, by one’s simple presence in front of the image, the episodes presented on the 5 screens of the installation, each viewer will construct a different portrait of the subject of the piece. The viewer’s investment in the piece thus determines what he or she sees and hears and in the end what they will learn or not about Raffi.

Faced with Time: Notes on a Fragmentary Portrait /

Albéric Aurtenèche

Are we surrounded by images or by screens? True, today one rarely appears without the other, and yet the two are not the same. The screen’s relationship to the image was once, in the first place, that of an obstacle, as something that blocks, separates, protects or filters; it naturally applied to the mechanical procedure of projection. The beam of light intercepted by the white screen revealed both the image and the screen, with the latter displaying no other concrete existence than that of a reflective material, often nothing more than a wall. In a context such as this, the screen was barely more than a virtual concept; since the advent of television, however, it has been seen as an object. This is even more the case today, when it can be carried in your pocket, when you touch it to activate it or hang it on a wall. In a word, as a corollary to the tremendous expansion of the world of images to which it gives us access, the screen has acquired a presence.

This is one of the issues addressed by Jean-Claude Bustros, a filmmaker whose work is open to the forms our relation with the image and the screen can take today. His installation Portrait de Raffi (1999-2004) puts into play five screens, including one LCD screen, three plasma screens and a projection screen: all quite different formats. Five screens which are quite present, then, because we can approach them or walk around them in a semi-circle; in short, we can situate ourselves in relation to them as objects on display which, given the position in which they are placed, surround us. Presence, in fact, is a relative term: we are aware of our own presence in relation to the topography of the place in which we find ourselves and to the position of the objects therein; and we are aware of the presence of the objects found in this place in relation to our own position. The role of the screens in Portrait, however, is not simply to mark out space, but also to recognise the viewer’s position: we are perceived by them in turn. Each of these screens, except the screen used for projection, reacts when a body enters or exits its relational field by altering the images on it. In other words, the screen brings about a mutual presence: the body that looks, the body that shows and the body being shown.

For the images in question here are indeed those of a portrait. This portrait, however, is more far-reaching and open than the term suggests. Historically, the portrait in painting or photography was the art of interpreting a person – whether by the artist or according to the model’s desires – in order to achieve the density required by the uniqueness of the image, of the point of view. The same is true of some kinds of literature, which, when it creates a portrait, suspends the narrative in order to give a critical description of a character’s main features. So-called classical cinema operates differently; since the 1930s, moreover, it has been obsessed by the art of the close-up. In order to maintain a sense of continuity between its images, it attaches itself to the bodies of these characters to such a degree that the portrait seems to have become its modus operandi. In fact, the cinema depicts bodies not only in space, multiplying images of them, but also in time, superimposing in (time) duration their reactions to different situations. This is how Raffi is revealed: not so much by an ever-increasing number of images as within a temporal plurality.

Unlike the portrait tradition, or even the documentary aesthetic as it is increasingly practised, Jean-Claude Bustros gives his gaze no marked orientation. We might even say that he has created a passive portrait. Bustros initially met Raffi because of the latter’s apartment in New York. When visiting the city periodically, Bustros would stay there, without ever meeting its owner, who was working in London. In frequenting this place, he formed an initial image of his host, like a prospective portrait which naturally dissolved as soon as they met. Little by little, and concurrently with the growing desire to document him, Raffi’s complexity and contradictions – we might even say his radicalism – became apparent. It was obvious that a linear documentary would not do justice to the multiplicity of impressions Raffi (was) is capable of generating in his interlocutor. The teleological progression and standardised format of a film require variation in the images and a narrative structure which creates a hierarchy of facts and organises them according to a dominant point of view. Portrait eludes this obligation by revealing itself to be more like a topological space and by allowing its subject to emerge beneath the gaze of the viewer and in relation to his or her body.

That this is possible is because Raffi puts himself on display. He does not give himself up to the eye of the camera but rather addresses it, challenges it, and through the image addresses the viewers, enveloping them in a voice which expresses him; he ends up depicting himself through his volubility. The installation’s strategy is thus to show the filmed material in almost complete form, cut into blocks of time with only the uneven bits removed. Of course, it would be mistaken to assert that there is no (editing) montage or selection going on: the moving image is framed, and right from the moment of taking the picture there is a question of choice, of a necessarily suggestive position. We are not yet an entirely panoptic age, and filming a body remains a matter of taking a defined number of shots of it. Nevertheless, what’s at issue here is to extend the time the model is on view, to accumulate temporal moments and not the bits of space which represent him. The blocks of time thus remain complete, Raffi’s speech continuous and the total length of the image longer than what any viewer, standing and free to move about, has the patience to view.

For this reason, each viewer will perceive the figure of Raffi in his or her own way, depending on their movements, on the way they deploy their body in the space of the gallery and in face of the time of the image. Each person visits the space of the exhibition the way they would the New York apartment, constructing their own point of view on the man who lives there – virtually – according to the information they want to find in it. The further viewers penetrate the installation, the longer they inhabit each room, the more Raffi reveals his private self. Raffi, moreover, is shown only in a limited area: in the same places which recur, like constants, he remains the prevalent variable. We might say that preference is given to presentational space over conventional representational space, over a multitude of images describing Raffi.

The temporal sections which make up the overall image are spread out over the three zones of proximity of the four physical screens. Thus, for each position of the viewer in relation to the screen, Raffi has a corresponding presence, in varying states. When the viewer is motionless in the tripartite area of reaction proper to the screen, the images flow past; while any movement will create a random cut and set another chapter in motion. As a result, anyone who behaves impatiently will perceive the arrangement of the installation above all else: the visitor’s relation to the screen appears when his or her relation to the image of Raffi comes to an end. In other words, here the person we persist in calling the viewer can take the form of a seeing body and an acting body, one surrounded by images and the other by screens.

Albéric Aurtenèche

Andrée Duchaine

Andrée Duchaine has worked in the visual arts area since several years. From 1974 to 1984 she was involved in setting up the video section at Vehicule Art Gallery and organized and curated VIDEO 84, the first international video encounters in Montreal. Mrs Duchaine curated several video art exhibitions in Europe, the United States and Canada. Between 1985 and 1995 she settled in Paris where she founded a short film distribution company. She worked with T.V. channels across the world.

Andrée Duchaine taught at Paris VIII, at the Université du Québec à Montréal and at the Ottawa University. In 2001 she founded a non-profit company Le Groupe Molior producing, curating and disseminating new media works.

Artist & work

Jean-Claude Bustros

Raffi

2005

Video installation

Biography

Self-taught photographer Jean-Claude Bustros started out in the genre of journalism, but rapidly moved toward a formal approach favouring the abstract and architectural volumes. He shows in both Montréal and abroad and was part of the dynamism that led to the creation of the Dazibao gallery. He gave up photography to study film at Concordia University. In the context of an experimental and broad approach to cinema, he attempts to convey the contrived nature of cinema and treats the film image as hallucination. Following his studies, he joined Main Film, a newly-formed group of independent filmmakers. He took over as Vice President, then as President. He also became the President of the national Independent Film and Video Alliance organization before becoming a professor at Concordia University.

Some of his films, such as La Queue Tigrée d’un Chat, Zéro Gravité, and, more recently, Rivière, have made a mark. Shown at such forums as the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Galerie Nationale du jeu de Paume in Paris, these pieces have been included in many festivals, programs and retrospectives all over the world. Throughout the 90s, he was involved in the emergence of digital media and, through Main Film, implemented one of the first training initiatives in multimedia for film and video makers in Montréal.

At Concordia University, he has been involved in the creation of the Hexagram Institute for Research/Creation in Media Arts and Technologies since its inception. He is currently pursuing his research in a cinema that transcends the screen, that is sculptural and present in space, in which he is already integrating interactive strategies.