A conversation with Dina Karadžić and Vedran Gligo

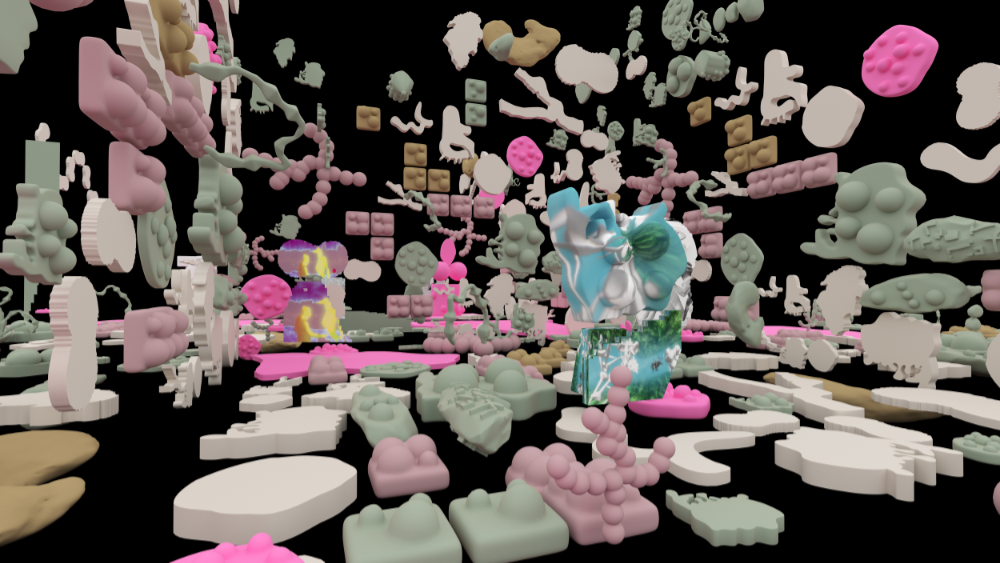

Pivilion is just one of the projects that encapsulates Format C’s interest in deconstructing digital systems. The main protagonists of this artist organization, Dina Karadžić and Vedran Gligo, conceived of Pivilion as an open-source gallery management software that supports free software, knowledge distribution and network decentralisation. With each iteration, it finds new social, spatial and digital relations. Its various versions and developments include web residencies at Schlosspost and mur.at as well as physical ones at Akademie Schloss Solitude and G-MK, an exhibition on a bus’ WiFi between Zagreb and Osijek, a few pavilions as part of the digital biennial The Wrong – New Digital Art Biennale, several gallery installations and WiFi exhibitions in Booksa and in various public spaces: all of them asking for the entanglement of an artistic and technical approach.

Irena Borić: Why was it important for you to create a gallery available through the Tor browser[1], and should this be understood as a quest for an art space that is not determined and defined by the commercial internet?

Dina Karadžić: Actually, Pivilion started as a need, not as a project. We basically wanted to show network-based or browser-based art in physical spaces but we didn’t really want to go through the commercial channels of the internet. I realised as an artist that I don’t even have the know-how to install the work without using a blog with a domain and paying for a server—and it really didn’t make sense to host networked art outside of the gallery that you are showing it in. Vedran and I understood that there is a need to figure out a way to construct this gallery so it can be hosted locally. Only afterwards, we realised that this is the methodology that we want to implement in our future work, and it would be handy to give it an identity by entitling it Pivilion.

Vedran Gligo: It was a quest for an art space that is not determined and defined by the commercial internet for sure. You can’t rely on today’s internet infrastructure that is freely available to people, because even if you make your own, you must go through various companies. If you decide to create your own server at home you are still buying a domain from somebody. We used the Tor project because it provides the option to do NAT punching[2] meaning you can host content behind your ISP’s residential gateway because most ISPs would not let you host your content from your connection. Tor does NAT punching out of the box, meaning that it sets up something of a reverse proxy between parties. There is a gateway between you and your content and the internet, and then it forwards everything that you are hosting through this network. This has presentation drawbacks. First of all, onion domains[3] are quite large and incomprehensible (which in turn makes them secure). The other problem is that Tor is often very slow because of its network design. It is not unusable, but it is slower than your average internet. It does work for multimedia art stuff; you just have to wait a little bit longer for it to load.

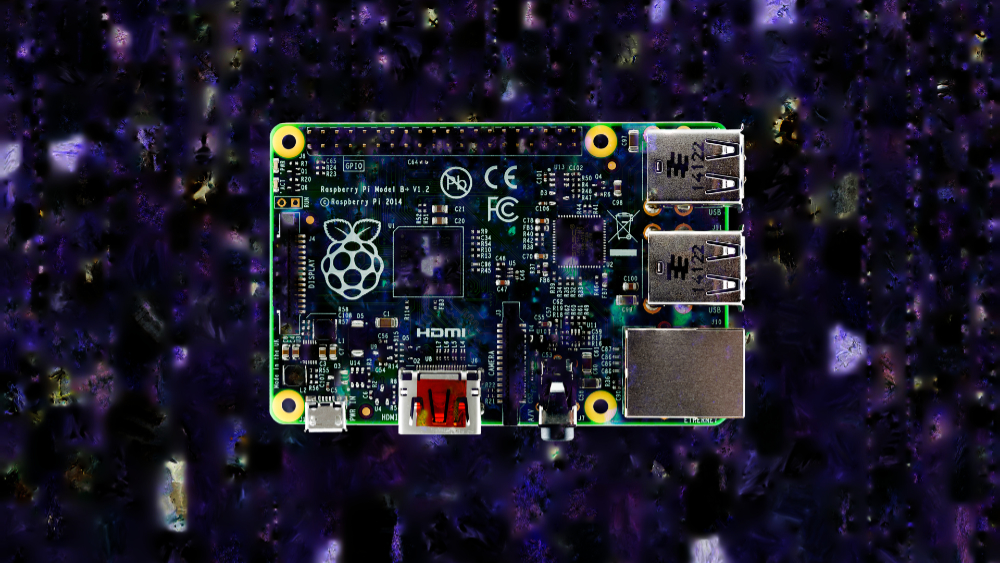

IB: Why do you find it important to use low-cost hardware such as Raspberry Pi[4], and how important is the DIY or DIWO approach here?

DK: The basis of our projects is to use free/libre open-source software and the least possible amount of hardware to create art, because we believe that digital art should be accessible and the production tools should be shared and open to anybody, especially for non-commercial purposes. We believe in not having big thresholds for people to access digital art and, in this way, more people can be provided with the means of production.

VG: Also, we chose to use the Raspberry Pi ecosystem because one of our goals for this project is to enable artists, who distribute their work through the internet, to understand how infrastructure works. Hardware like this seems perfect because you are not limited. If we had chosen to use a phone, it would be just like a downloadable app. You would download it, click and host art from your phone. But then it becomes more of a product and our project is not a product, it is about gaining knowledge.

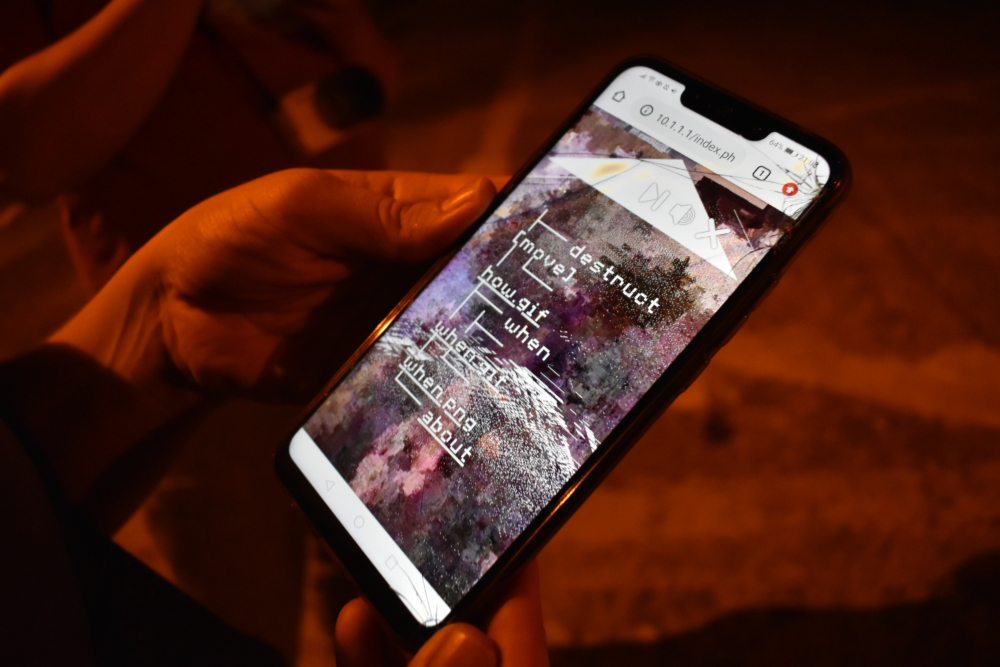

DK: It is important to note that Tor network is not the only network that Pivilion is capable of. We also do a great deal of work with local networks, so it becomes its own WiFi server, and we make exhibitions accessible over local wireless networks.

IB: One of the latest WiFi exhibitions, #pivilion_dot_net at Gallery Prozori in Zagreb (spring 2021) was based on a spatial installation composed of server sculptures that emit their own local WiFi network, which means that in order to view the exhibition you need to be present in the space. Why did you insist on doing this exhibition on the physical premises, especially when a lot of cultural content migrated online due to the pandemic conditions?

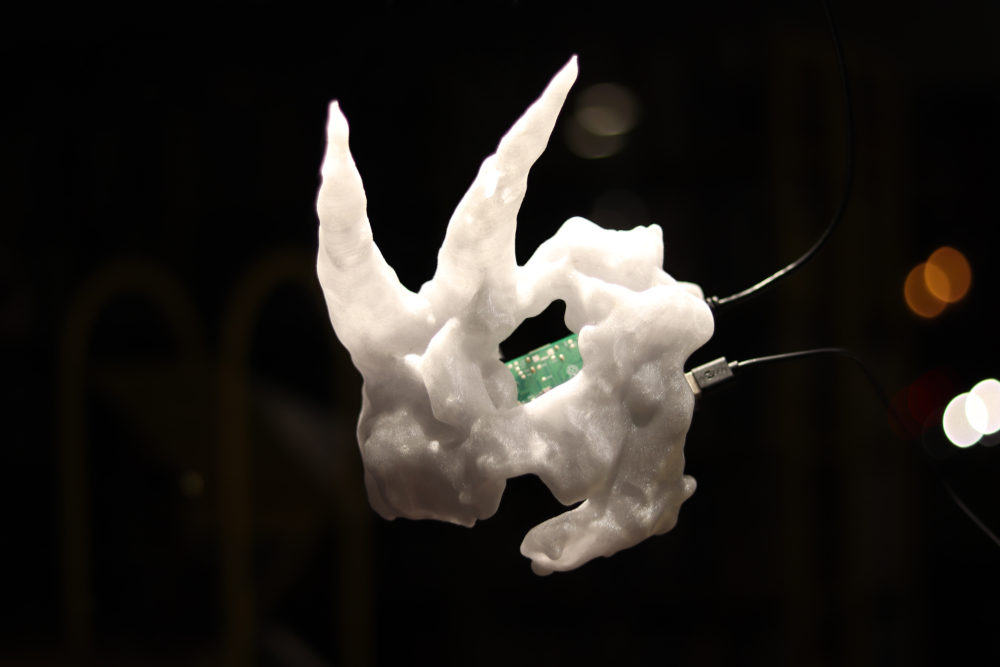

DK: We are constantly creating both micro and macro community situations where we install the network content in a physical space. We had been doing this before the recent global health crisis, so we wouldn’t necessarily create an online adaptation because for every iteration, there was already a community that we wanted to work with. That was also the case with the Prozori gallery space (which is a part of a local library). We always try to share our collective awareness about the ethics, the politics of networks and the internet in order to provide an understanding of why independent networks are important. Like why is darknet better for showing art—it is much harder to use, the experience is much slower, so why would anybody do this? We recently interwove this idea of local network objects with sculpture. We wanted to connect a sculpture with hardware in order to reduce the amount of commercial hardware and equipment in our art installations. Our “server sculptures” are enclosed in 3D printed generative parametrically modeled objects. They are the result of a collaborative process in which we designed and produced these sculptures to serve as a visual representation of the servers.

IB: For each exhibition, you collaborate with impressive artists who are recognised within Croatian contemporary art scene, whether they make digital or non-digital works. Sometimes the artists you are collaborating with are creating online work for the first time, and from the curatorial perspective, the selections and invitations you make are very intriguing. How do you perceive your collaboration with artists, how do you see your curatorial role?

DK: We are curating from the position of a fellow artist. As artists we choose to undertake the administrative and technological efforts in order to create a good situation for more people to work in. I feel the answer is quite complicated, and this is because of the format of our artist organization: it is formed for advancement, but not to advance just the self. We build these projects to advance together and to support each other. I don’t know if I would call it curating.

VG: I mean it is definitely curating, but it is not what we want to do. This is not our goal, we are kind of being forced into the role. So, our artist project is making us become curators in a way. We are now contemplating doing more of our own art on this system. Because we are handling infrastructure more than we are handling art.

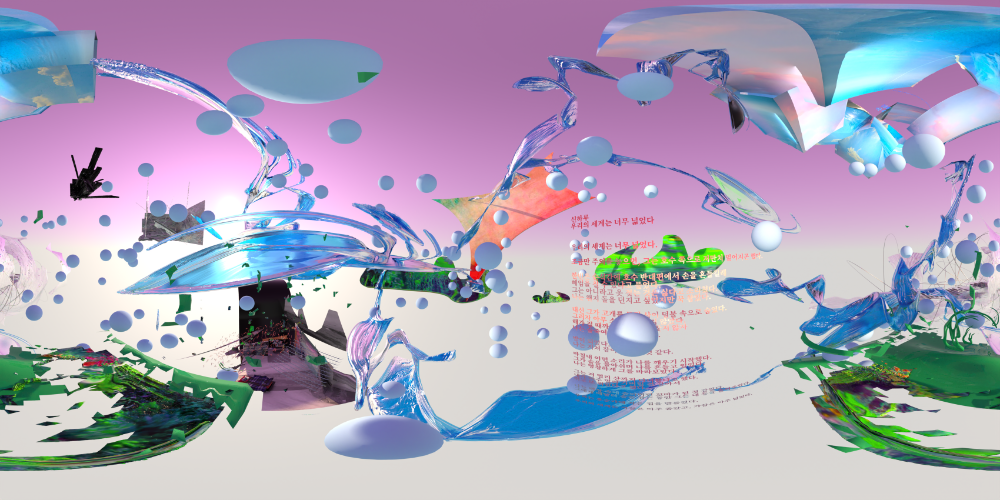

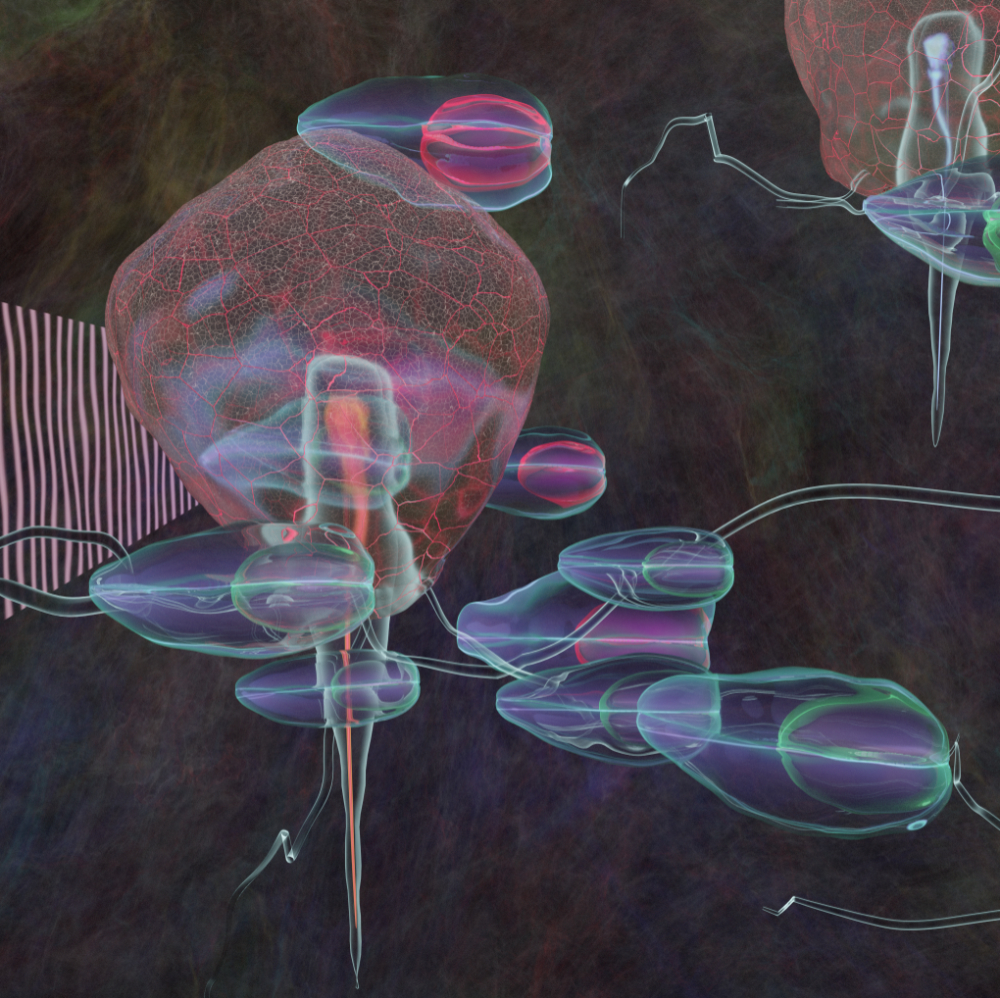

IB: You have also used the infrastructure of the Pivilion project for your own artistic work, A triptych on tectonic transgressions, that took place within three wireless network access points in a public space in the town of Korčula with the support of grey) (area organization in 2020. How did the infrastructure of Pivilion become the most suitable mechanism?

DK: We were considering how to make an open and accessible piece. With grey) (area not running a physical gallery space in 2020, and because of the pandemic, it really didn’t make sense to gather people in closed physical locations. Korčula, gorgeous as it is, is a real tourist attraction so our audience was predominantly people who may have not expected or even intended to interact with our work. We could jokingly say that because Pivilion shows up as an open WiFi hotspot without password protection, it’s kind of an art honeypot[5] for an audience only wanting to get free WiFi—and ends up in a digital media art gallery “by accident”. So, in collaboration with grey) (area, we decided to make these Pivilions accessible at three locations but not confined to a physical space—you would only have to join an open network in a public square to see the three-part piece. Thus, the Pivilion’s infrastructure became the most logical way to share digital art with local communities.

Dina Karadžić lives and works in Zagreb and online. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (MFA) in 2012 and has been a member of the Croatian Society of Fine Artists (HDLU) since 2011. She joined the Croatian Society of Self-Employed Artists (HZSU) in 2018, and has led the Format C art organization (an organization that focuses on digital art, multimedia experiments and collective creation) since 2014. She actively (co)operates in the field of new media art, initiating events and exhibits in the fields of visual, digital and online art.

Vedran Gligo is a self-taught DIY hacker, artist, organizer and project manager. In his everyday practice, he uses the principles of open-source software. He is active in the local community, organizing free and open digital workshops in Zagreb’s AKC through the hacklab01.org project. He works in the field of free culture, promotion of the GNU / Linux system, glitch creation, participatory online art, independent cultural production, hacktivism, etc.

[1] Tor is free and open-source software for enabling anonymous communication.

[2] Hole punching (or sometimes punch-through) is a technique in computer networking for establishing a direct connection between two parties in which one or both are behind firewalls or behind routers that use network address translation (NAT).

[3] .onion is a special-use top level domain name designating an anonymous onion service, which was formerly known as a “hidden service”, reachable via the Tor network.

[4] Raspberry pie is a tiny computer that you plug into a monitor and to which you attach a keyboard and a mouse.

[5] In computer terminology, a honeypot is a computer security mechanism set to detect, deflect, or, in some manner, counteract attempts at unauthorized use of information systems. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honeypot_(computing), 17th June 2021.