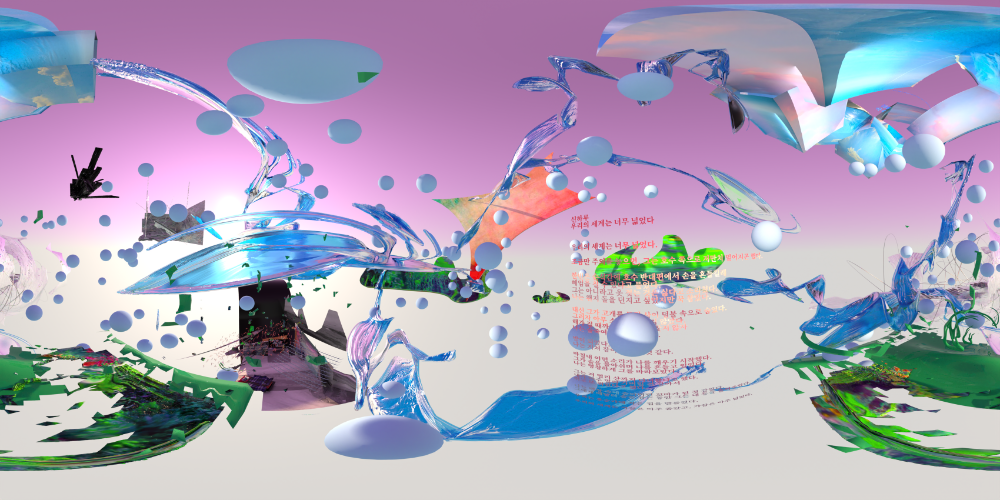

The symposium Rethinking Our Futures: Art and Collaboration made it possible to shine a light on an important issue regarding the production and presentation of art in a society that increasingly relies on digital technologies. Our intuition tells us that the digitalization of our social relationships, geography and lived experience will profoundly transform how we relate to the world, to others, to time and to space. The passage to an all-encompassing pandemic online mode has greatly accelerated this transformation: this tsunami of changes will carry the creation and dissemination of art along paths that are riddled with new constraints and perhaps will even redefine art itself and our relation to it. Without going so far as to attempt a philosophical and sociological redefinition of artistic production in the digital age, our modest contribution aims to identify where and how those who build and sustain the artistic ecosystem can set up spaces and mechanisms within it. This will enable artists not only to appropriate digital technologies, but above all to reaffirm and strengthen their critical reach, which is essential to the arts.

Unlike the technological revolution that took place from the 70s to the 90s, which was centred on widespread accessibility to electronic machines and devices, the digital revolution is only minimally concerned with access to equipment. With regard to digital technology, the foremost issue today is the availability of expertise and know-how. In fact, although access to computer tools and the Internet has been vastly democratized, there are still very few people who know how to use these tools to code and develop original projects. In our view, learning digital know-how is the biggest hurdle that the artistic milieu needs to overcome to truly appropriate the digital. This expertise is rare and highly sought after, and it commands salaries that are incommensurable with those paid in the cultural milieu. Moreover, the specialized training required to develop this expertise does not include the basic knowledge conducive to cultivating a sensibility to artistic production. The particularities that distinguish art projects from other human endeavours cannot be ignored or misunderstood, especially by those who participate in their production.

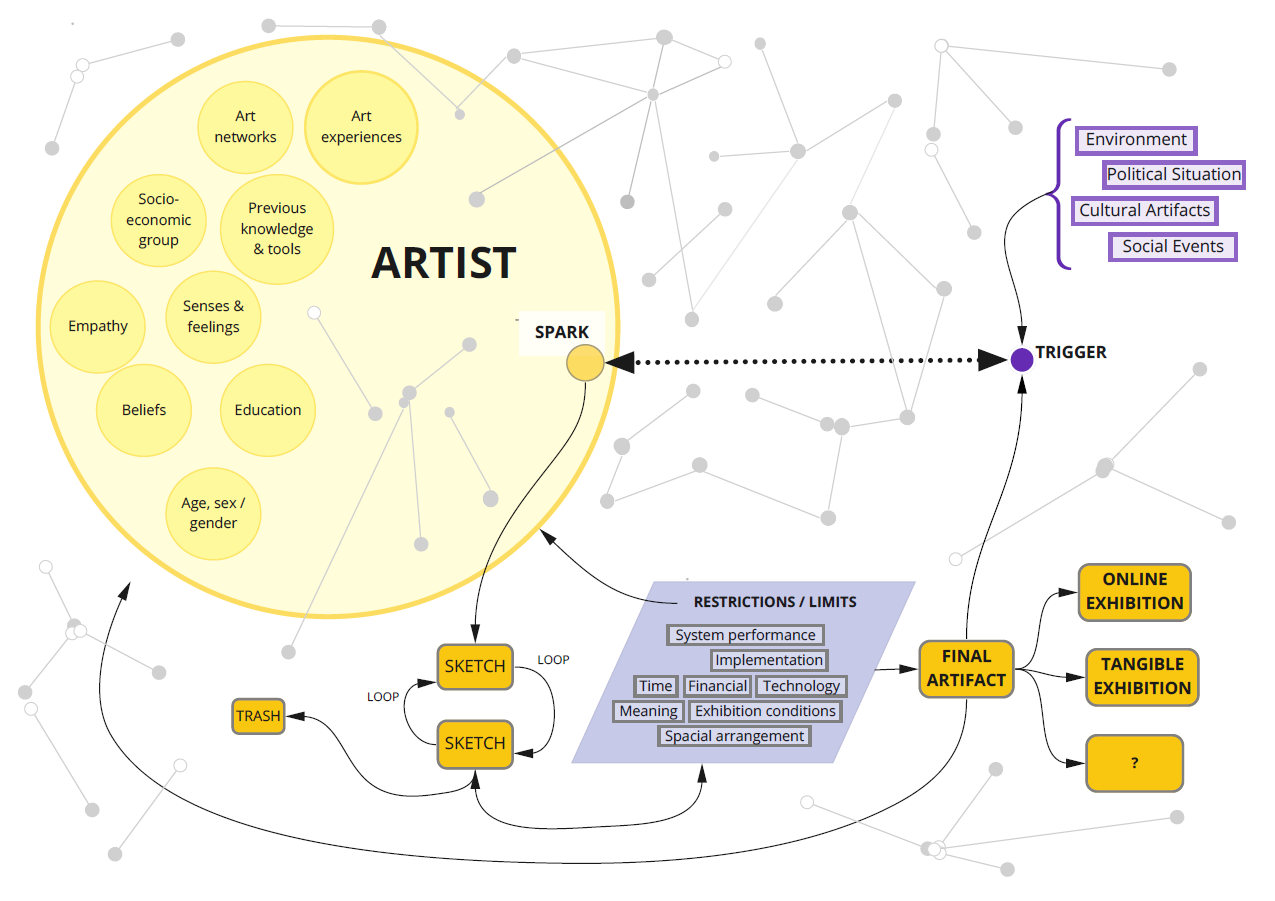

We would also like to point out the substantial gaps between the operational modes of big teams of specialized programmers who work on major digital projects and the methods of artistic production that require time for experimenting, iteration and freedom to think critically. In addition to these issues, there is also the matter of financing artistic models in which artists conceive of, develop and also may produce the works, which is indicative of the broad discrepancy between what artists have access to for creating their art projects and what utilitarian productions can draw on for support. What we have here is the perfect recipe for extinguishing the artist’s path to the digital world.

These observations compel us to rethink the operating methods of the milieux that support art production. And it appears urgent to do this, taking into account the importance of this expertise in a digital world, but also for the impact that this has on the whole value chain (business term) or the entire range of activities needed for artistic creation and dissemination. We are aware that this question of value may seem quite simplistic in the context of an artistic reflection that leads more agreeably to aesthetics and sociology. However, in our view, this is the lynchpin whereby we could integrate artistic creation, its critical outlook and ways of working within the digital ecosystem.

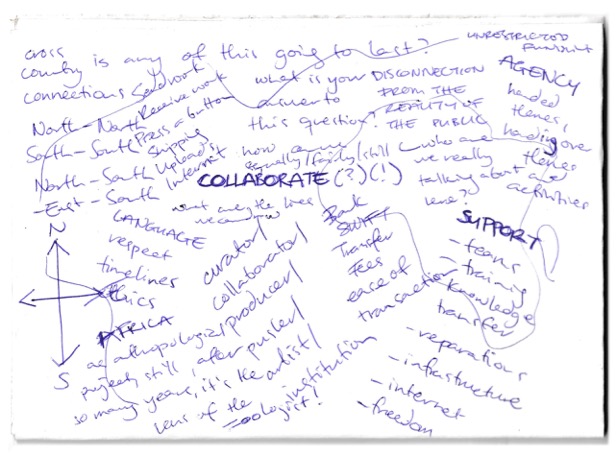

The global pandemic has pushed the entire cultural community onto digital platforms. For contemporary art production and dissemination, these platforms quite often are just a pale imitation of artistic experiences. This forced momentum towards the digital has also affected the whole artistic ecosystem, from managers to curators, to communication departments. Interweaving the digital into work processes is likely to become something far more lasting. This transformation of entire working processes leads to gains in efficiency, but also to additional costs. Expertise in cloud computing, networking technology, organizational transformation, management and collaborative development is currently a broken link in the artistic ecosystem’s value chain: the numerous sums of money that it swallows up either do not reappear in the artistic milieu, or only partially so when the expertise is that of recipients from the milieu. To ensure the artistic milieu’s true appropriation of the digital, this leakage must be plugged by integrating the expertise directly within our ecosystem. This means hiring and training our own digital experts and specialists in organizational accompaniment, experimentation and artistic iteration with the aim of making their expertise available. Given that the Canadian artistic community is principally made up of small and medium-sized organizations, and that artists do not have the resources they need to individually hire programmers or developers on a regular bases, only a collective and self-run approach will make it possible to reach this goal. The development of such initiatives, whether territorial or sectorial, will not only make our milieu technologically self-sufficient, but more importantly, it will ensure affordable and enduring accessibility to expertise for artists and arts organizations, specializing in the development of cultural projects. To fix this broken link in the artistic value chain, to appropriate part of the digital economic system and to design a parallel system by and for artists, will ultimately enable our milieu to adapt the digital to our criteria and our operational modes. And even more importantly, to assert our voices and critical views by constructing a contemporary digital imaginary. A final observation worth highlighting concerns the impact that this type of collective approach would have on the roles of our organizations and the people who work in them. We briefly focused on problems linked to the ideal of the artist-programmer who has the ability to pursue a solo creative practice. This ideal is problematic in several regards: it is highly exceptional—and inaccessible to the vast majority of artists. We believe that it represents more of an impediment than an opportunity for the artistic milieu’s digital appropriation. Considering that digital technologies are intrinsically collective, cultural digital projects therefore must be envisaged as team projects. This passage from the individual to the collective will in turn bring about a transformation of the role some of us play in the artistic ecosystem. Digital appropriation and collaboration with specific forms of expertise will lead to the notion of accompaniment and intermediaries. In fact, the presence of someone in charge of translating languages, a priori aspects and ways of doing and seeing will become a necessity to ensure good mutual comprehension among team members. Over the course of the accompaniments, this person’s knowledge of the possibilities, pitfalls, imaginaries, tools, currents, approaches and languages will provide him or her with a very broad vision of contemporary digital artistic production. Is it conceivable that today’s curators, those interested in digital issues, will broaden their practice and add the roles of knowledge guardians, experience mediators and accompanying persons: will they become the intermediaries linking artistic and technological issues? They would probably be the ones who are in the best position to do so and many, without being fully aware of it, have already taken on the role.