Interview with Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás and Béla Tamás Kónya

Béla Tamás Kónya: What could we agree upon regarding the main question of our symposium talk for Molior?

Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás: From my perspective, there were very relevant topics discussed throughout the symposium. In my opinion, the connecting realities, thinking about different aspects and impacts of artificial intelligence and virtual reality on curatorial and museum work was particularly interesting, in relation to our professional fields and interests.

BTK: How did you gain so much experience in this field and when did it start?

LNR: That’s pretty hard to say. The interest has always been there. But it hasn’t always been that obvious to curate in an entirely digital mode, it was rather the pandemic that brought me to this direction as well. Although, I have been working with art that reflects on new technologies, information, technology, and computation for a long time.

How about you? When did you start to be interested in digital art?

BTK: I first started focusing on media art and its conservation in 2015, when I realized that one of the artworks at the Ludwig Museum in Budapest could not be restored and a condition report could not easily be made because it was a media artwork. It was Péter Forgács’ Danube Exodus, which has been part of the Ludwig’s collection since 2009, and there were several types of channels to connect and link with a touch screen. After that, we had no kind of professional description or any kind of instructions to install the art piece outside the infrastructures of the Ludwig Museum. We would have needed to ask the artists to be a part of the installation process every time. Of course, we recognized that it was not sustainable. The Ludwig Museum and I started to talk and think about how we could save and conserve media art and what the role of the conservator is in this field.

LNR: Well, it is developing. So I mean now that you are working in a bigger institution than the Ludwig Museum you might need to reflect on this change that has been brought about by developments in information technologies, maybe not only in art production and preservation but also its mediation?

BTK: Yes, we need to start thinking about and developing ways to transfer and change the Time-Based Media collection of Budapest’s Museum of Fine Arts, where I now work as a Chief Operating Officer. This doesn’t only mean digitalization—making a digital copy of a physical piece—, it also means digitization—creating tools that are first and foremost digital, and often exclusively digital. We might be able to create new kinds of metadata and new solutions to change the meaning of digital pieces. It does not mean that we have to do digitalization for marketing purposes only. It means that this is a new field for collection management. The conservation treatment for the artworks during the diagnosis processes will eventually involve many new types of digital files of the artworks that will be created by the main diagnostic research or software instruments . We might need to link or relink this information to the Collection Management System, and it needs to be handled properly and made available to researchers. This requires a new way of thinking for institutional organizations. Day by day with new digital solutions and new digital thinking, new positions and departments could be developed within the museum, such as a digital department or a digital director position or even a position for someone to handle and create user experience processes for digital curating.

LNR: It’s an interesting development, especially in big institutions. I don’t know if it has been triggered by digitization and the development of technologies, but later research and development departments in certain institutions have started to emerge; some of them do research on the impact of digitality in curatorial work, art mediation, and art production. I realized that this is something utterly needed in museums, especially institutions of the scale of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. It is important to note that these departments are not engaged with the collection per se, rather with methodologies for mediation, with the way of conveying curatorial messages, while keeping up with the newest technologies.

BTK: Yes, and have you ever thought of digitization as a new part of 21st century social processes ? It’s kind of a new era and a new way of thinking, which was just accelerated by the COVID pandemic.

LNR: Yes, the pandemic accelerated many processes that are linked to digitization. For example, I would like to mention a project that I’m working on right now, which is called BEYOND MATTER. I had already developed this project on digital art mediation before the pandemic. In 2019, it seemed to be a nerdy marginal topic, but now it turns out to be central for lots of museum professionals, as we realize that a museums’ locations are not just defined by their physical walls. They might be somewhere else, or maybe nowhere. Digitization expands museums and displaces them. Maybe this is how I would describe this in this new experience, the displacement of the engagement with art.

BTK: You had been developing the topic of BEYOND MATTER at least three years before the pandemic, right?

LNR: Yes, I started in 2017.

BTK: Was it a new kind of experience for you during the pandemic? Something that you had never thought of initially?

LNR: Throughout the first lockdown, I was immersed in the incredible abundance of examples. Before that, you had to research for days to find examples for digital experiences offered by museums, and usually, they were very shaky and not well elaborated. It was really hard to find something engaging. From the beginning of the lockdowns, many museums started to work with digital formats, thus the number of positive examples started to increase. That was an interesting development. For a while I was quite immersed in the research of what others were doing. It has been very useful for my practice.

BTK: You’re right, that’s also what we have been thinking about at the Museum of Fine Arts. The Museum shared its own experiences on many news and social media platforms in 2020, such as Twitter, YouTube, or podcasts, which was part of a new interest for ways in which museums could share information with a broad public. It’s a really new, dedicated, and special way to work with hybrid museums. During the pandemic, and with the emergence of digitization as a tool for prevention and collection care, this kind of art conservation was such a new and risky field. Fewer visitors means less interest and smaller crowds in the museum. Museum employees working from home and the museum buildings being closed to the public also meant that we had to think about biological hazards like beetles, mites, and mice, but also dust. This required more actions and different preservation care. Because we know visitors, we know the open area, the interest and focus is not the same way as during normal life. What I wanted to say with this and what I wanted to share with you is that the museum still has problems with the physical artworks and still has to dedicate professionals to care for the material art, not only the digital elements. It goes hand in hand. Digitization and digital materials cannot substitute material artworks.

LNR: Sure. Digital experiences will probably remain an addition. They imply additional labor for the institutions because these hybrid experiences and solutions need specific commitment from museum professionals. I’m not sure yet how it’s going to play out after the lockdowns, but some of the digital formats are likely to stick around, while some will fade away. At least this is how I see it, but how about you? You previously talked about new hybrid solutions, which will change exhibition experiences at the Hybrid Museum Experience Symposium (HyMEx), which was organized by the Ludwig Museum and the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe (ZKM), and which was a continuation of the symposium that you initiated at the Ludwig Museum earlier, the Media Art Preservation Symposium (MAPS). With the HyMEx, we broadened and opened up the topic, partially triggered by the pandemic, that you raised with MAPS. You’ve already shared some insights at the conference, but now I’d be interested in your predictions.

BTK: Yes, you’re right. MAPS, which was held yearly between 2016 and 2020, and HyMex, which pushed the reflections further, were a site for discussing media art preservation and critically thinking about problems in the field of media art. HyMex opened these topics for museum experiences, which also involved issues relating to digital content. It’s not just the main problem of how we can transfer and change our life through digital means, but also how we can share, how we can keep digital information and details for the future. Items can become obsolete very easily. How can we know which of our digital information pieces and digital files can be played or used in any new device or applications, five or twenty years from now? These kinds of reflexions are led by internet providers and big companies who can change their platforms and file types very quickly. One of the main issues will be to find a professional person, or possibly a professional application, to prolong the life of our information and to personalize digital files for the future. Maybe in the next couple of years, this kind of work will not be handled by a person, maybe it will be handled and conserved in a digital way as well as through automated solutions.

LNR: That’s a very intriguing approach! What came to my mind while you were talking about the future is preservation, specifically the relatively new digital methods of preservation. Throughout HyMEx, we arrived at the question of sustainability, raised by Sarah Kenderdine. The point is that digitality, even if it seems to be, is not immaterial. It requires a vast amount of energy to keep data safe, and the accumulation of data happens at a high pace. All this digital art production is contributing daily to this huge mass of data. Again the question of what to preserve comes up, why, how to choose, and how do we make this sustainable?

BTK: Do you think digital and digitalization strategies could be a solution for institutions to maintain digital contents?

LNR: On the one hand, of course, but on the other hand, the institutions won’t be able to solve the problem alone. Lately, several artists are creating work on the interconnectedness of digitality, of the stack, or the material basis of information technology, and its relation to ecological consciousness and sustainability issues. One could think of Joanna Moll’s online works, Emma Charles’s documentary, White Mountain (2016), or Tega Brain’s recent projects. These artists are pointing out that our resources are finite, but it’s hard to find a sustainable path, at least I haven’t seen any. Although this is something we shall address on an institutional level, and make plans on how to digitize, on what to keep, and what not to keep. Have you thought of this particular aspect now that you are also dealing with thousands of artworks? The collection you’re managing—even only the related metadata—has a vast ecological footprint.

BTK: Yes, you are totally right. It opens up thousands of new questions, such as how we think about digital files and digital metadata within the existing organization of the museum. People can easily imagine that digital content means everything inside the museum, and dealing with digital processes simply means solving everything with a computer. It’s more complex and involves a lot of processes. Digital materials and digitization also mean the museums could be transferred as digital museums, which require different solutions for many aspects, such as collection management and creating agreements and contracts, but also developing Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems to handle the visits or hyper-personalized content for the visitors to be engaged. I’m not only thinking about newsletters or posts on Instagram, but content that fits an individual visitor’s interests or involves the visitor in the solutions the museum is looking for to solve its problems, or even the creation of new exhibitions. This also has an impact on broader aspects of the museum’s work like contracts and agreements, newsletters, and records of various kinds. So we might change the way we think about the digitization of paper, of information at large. It’s not the same as the digitization of an artwork. Given the digitization of processes, this begs the question: how can we make a project while thinking about digital tools and platforms from the start?

LNR: If I’m not mistaken, in your understanding, this digital platform is becoming a parallel world to the physical museum?

BTK: Yes, everything could be transferred in an experiential digital way, as a digital museum.

LNR: One can imagine this as a sort of digital twin of the physical museum…

BTK: Definitely. We could have an analog museum with objects, and also a parallel museum with the same name, with the same highlighted pieces and artworks, but transferred digitally. They would be two separate museums that would each require specific professional handling.

LNR: Is this something you’re working on right now, to manage the digital twin of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest?

BTK: Yes, this may be the next step for the future: thinking about how we can separate digital artworks from digital paperwork. In this field, there are already automated and simple ways to do this. The more managerial aspect and the issues that this part of the digital question involves are a separate problem from the digital conservation of artworks. They each require dedicated professionals and solutions.

LNR: Of course. You will probably need to migrate the aura of the artwork as well. As you mentioned digitizing documents is not a major challenge, but artworks are different: they are supposed to have an aura. What happens with the aura if the artwork gets digitized? Some believe that it migrates. For example, Adam Lowe often discusses the migration of the aura in his writings, among others in the publication The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality (2020). Others say that the aura always remains with the original and it’s impossible to shift it to the digital realm. The point is that there are various points of view regarding this. Walter Benjamin’s essay on mechanical reproduction in the 1930s established the notion of the “aura” specific to an artwork, which gets lost in mechanical reproductions. Now we are at a point where artworks can be digitally reproduced in a very precise manner. One can scrutinize and investigate the painting or any other artwork much better via a high-resolution digital copy than in real life. The question is whether the aura of the artwork can or cannot be transferred with a digital copy or a digital twin?

BTK: It’s a really difficult question because, as time passes, through experiences, sensory acuity can get very sharp when it comes to the use of digital forms. Twenty years ago, when you bought televisions with a 3:4 aspect ratio and a low resolution by today’s standards, you still felt like this was the highest possible resolution . You felt the images were sharp and perceived them as very high quality. Nowadays—now that 4k or 8k high-resolution and 16:9 aspect ratio are standard—we can laugh about how twenty years ago, photography or video recording resolution was nearly nothing. You cannot zoom or change that older content to higher resolutions. Today we think in the same way: that these are the highest resolutions possible or at least the sharpest we’ve ever experienced, and we can’t imagine anything better. But what will it be in the next 20 years? What should we do to create and make the highest resolution possible of the files and also provide these records for the museum archive, for the data warehouses, and for our IT specialists? How can we keep and store metadata for the future? This could be high-resolution files and content, which can be transferred to higher resolutions in the future.

We have several examples. For instance, in 2016, we wanted to show an exhibition of a piece called h.l.m.v 2.0 (2005) by the Hungarian media artist Marcell Esterhazy. At the time the artists made programming files on Adobe Photoshop with the highest resolution he thought worked for 2016 projectors and media players. Then in 2020, we noticed the work was shaded or it felt like it had a filter over it. That was because HD projectors now had a much higher resolution then four years previously. We luckily owned the original photographs and, in the end, we were able to make a new version of the same artwork with a higher resolution. We also worked with the artist to create an authentic way of preserving the art. Still, it’s problematic to have to work with the artist every time. It requires resources and time. This is the critical part of art conservation for older artworks since you are sometimes no longer able to contact the artist.

I have yet another question. What do you think about digital museums and digital exhibitions? Is it a kind of transition or a parallel way in which museums could exist?

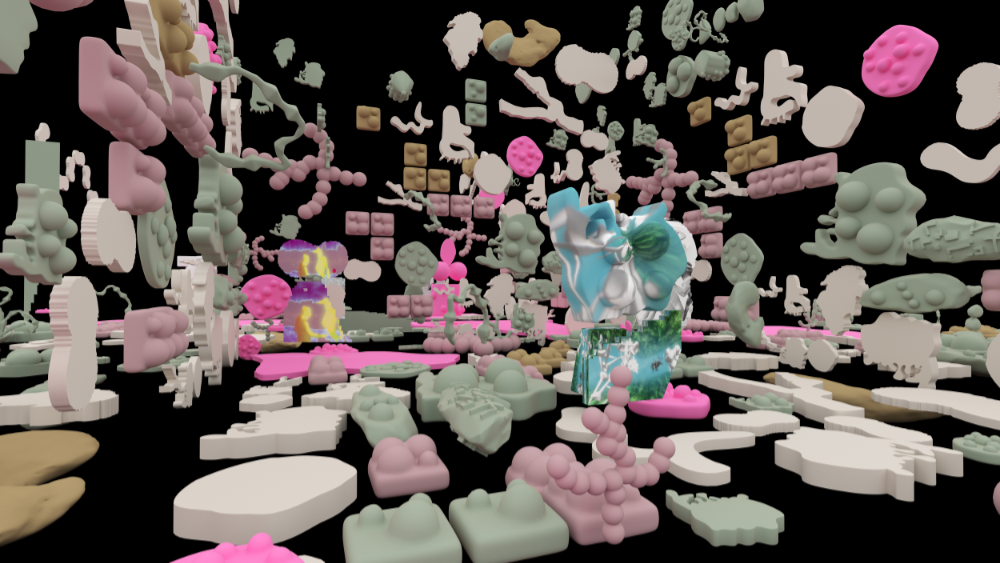

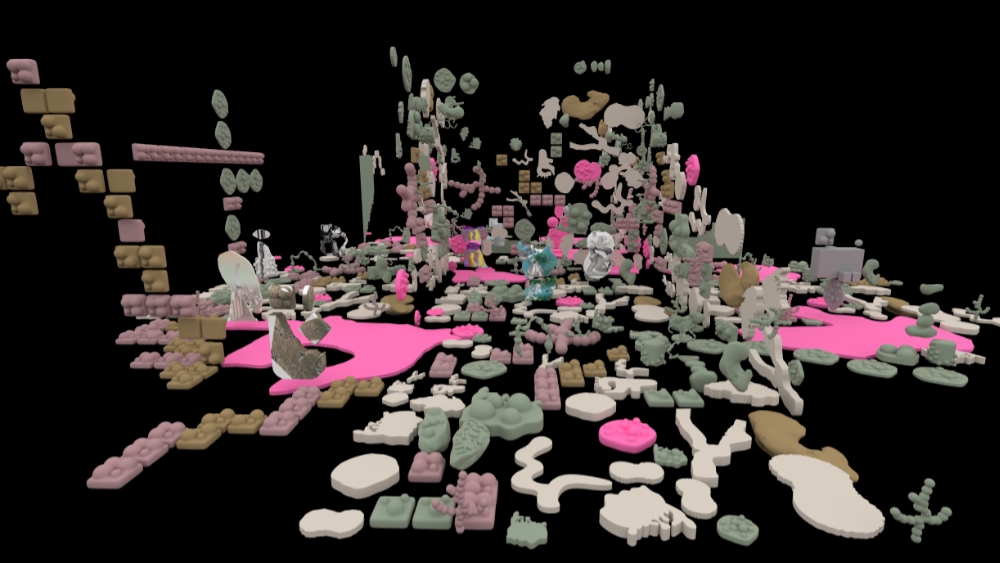

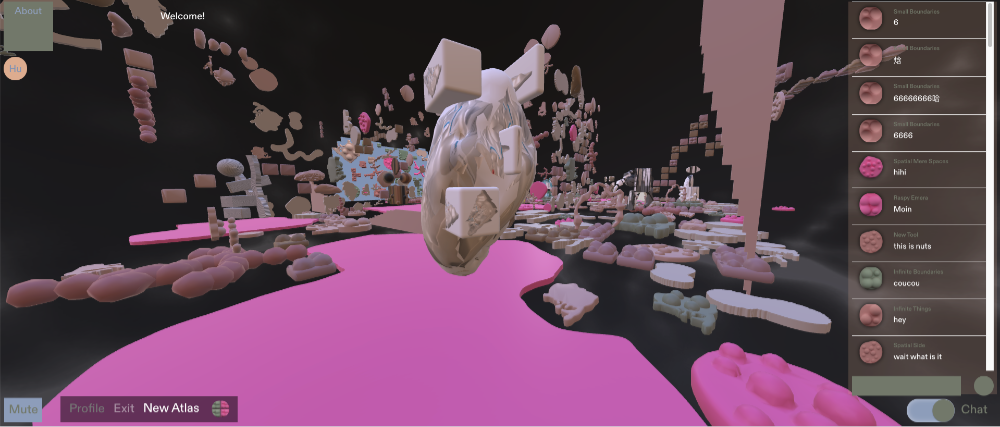

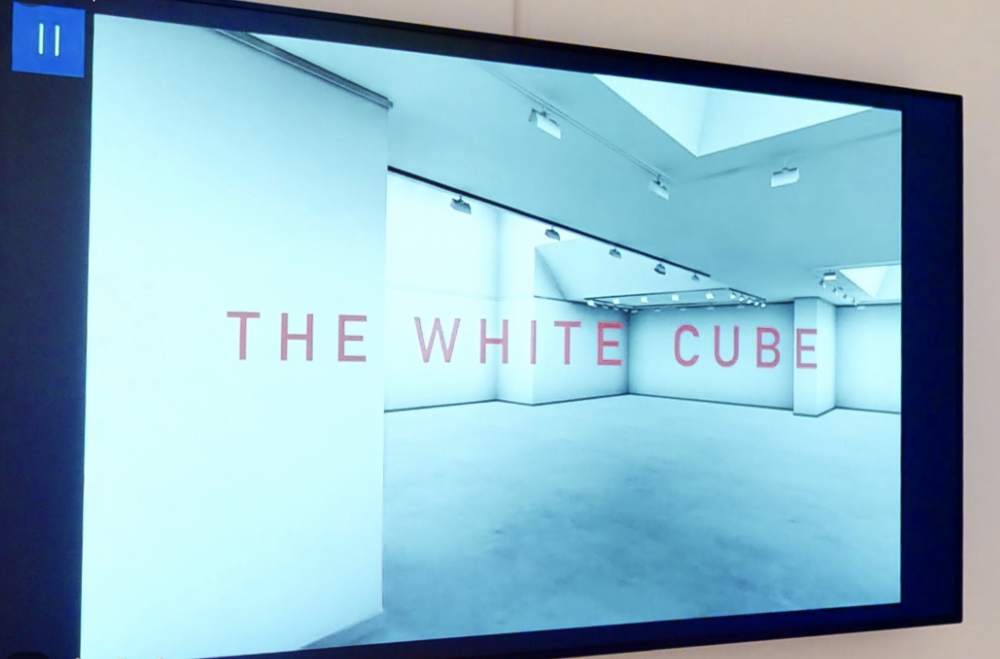

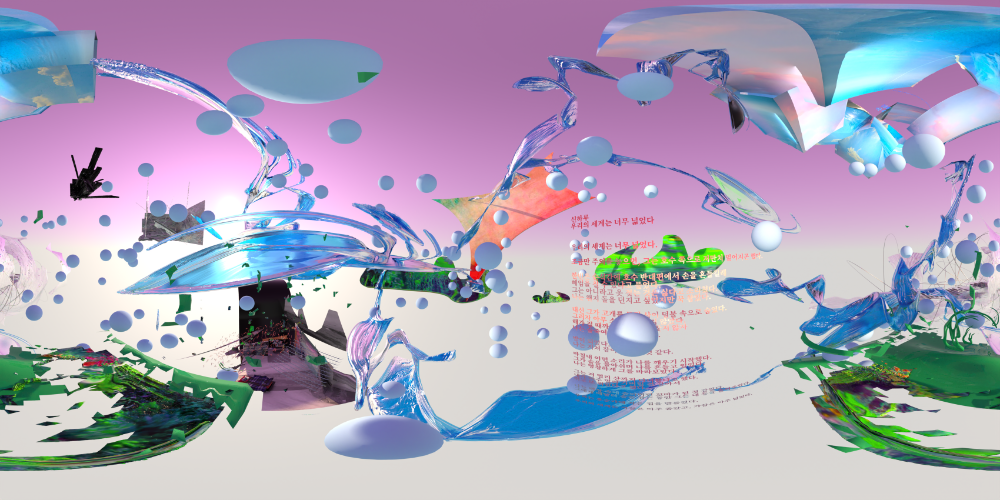

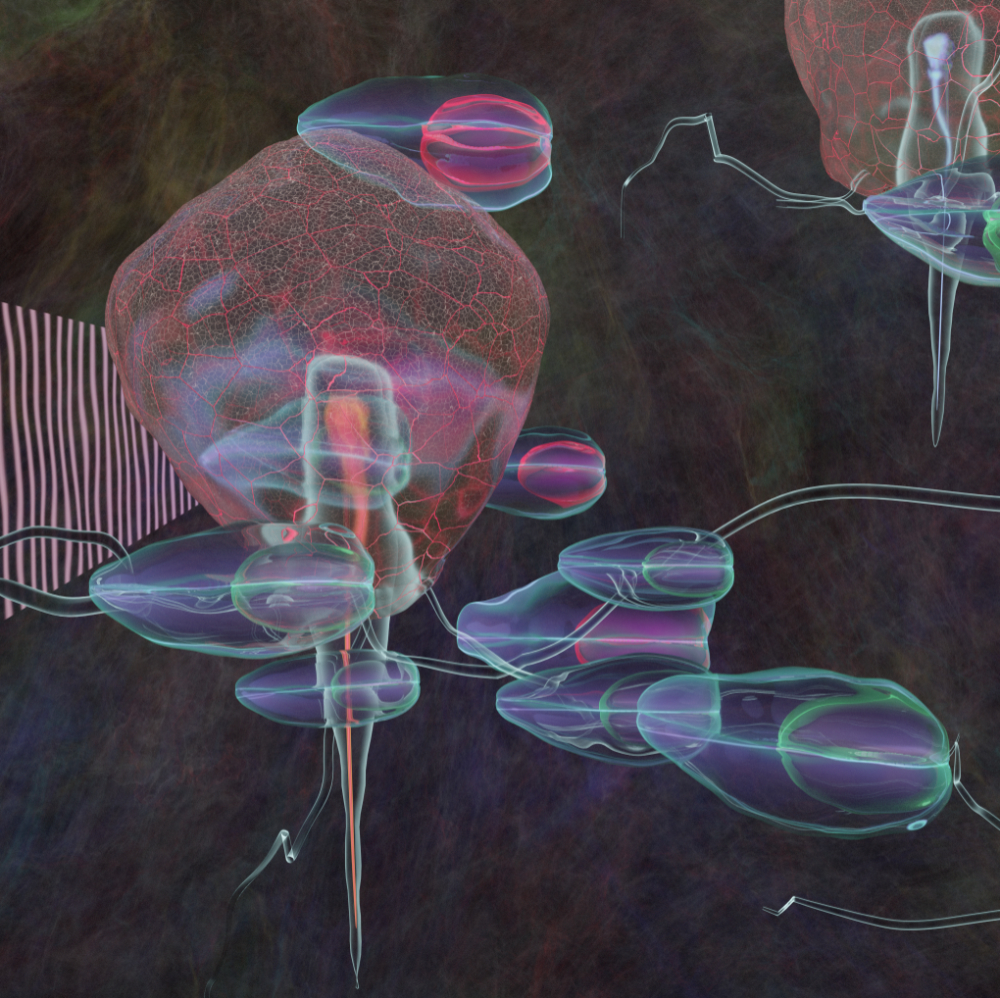

LNR: It’s a complex question, let me answer with a case study: an exhibition that was recently on view at the Ludwig Museum Budapest, and still online, entitled Spatial Affairs, that I curated together with Giulia Bini. It is an exhibition on different approaches towards the notion of space throughout the 20th century up until today. The exhibition space is understood here as a white cube populated by various artworks that reflect on information technology and its societal impact, rather than using information technology per se. In the exhibition, you could see manifestos of artists, sculptures, prints, drawings, videos, and so on, not only code, or computer-based artworks. If one followed the narrative and scenography offered by the physical exhibition, the last piece one encountered was a video by Adam Broomberg and Guy de Lancey, entitled The White Cube (2020), with Brian O’Doherty reading from his seminal book Inside The White Cube (1976/86). The video is based on renderings of computer-generated, three-dimensional white cube spaces. The artists eliminate and at the same time elevate the white cube and also criticize it with this approach. Spatial Affairs is in line with this criticism of the white cube by digital means. We included net-based artworks, not in the exhibition space, but in a completely new digital environment. Right from the start, we meant to show browser-based artwork online, in its natural habitat, not in the exhibition space itself. But a digital space was necessary to stage these works, thus a complete environment evolved from the process that we created together with the design studio The Rodina. They created Spatial Affairs. Worlding – A tér világlása from scratch, which became an antidote to the white cube: a possible answer to the question of how art shall be contextualized, curated, and mediated in a digital embedding that is spatial. We display the artworks in a new type of environment, very different from a museum building, but still walkable because we think spatial experience is a crucial element in the reception of art. Spatial Affairs. Worlding is a conclusion of our experiment, but not the only valid way to approach digital embedding of born-digital art.

BTK: This is a very interesting and new way of approaching art curating and digital curation. What do you think about this change of process, which also involved the evolution of collection and user needs? Do you think that visitors and the communities changed the way they think about artworks or exhibitions after the pandemic?

LNR: That’s a great question! It’s something that I cannot say off the top of my head. It is still ahead of us to evaluate the new approaches, and figure out what we can do better.

BTK: Yes, I don’t have an answer either. During this year, the value of thinking about digital issues and the life of digital display has changed day by day. It’s really up to us to reflect on ways to prolong the life of digital objects and data. We could be well prepared for what is to come, I think, by just facing the future and fastening our seatbelts.

LNR: That’s a very fitting closure.