A conversation with Oh Youngjin, Director of Erangel: Dark Tour

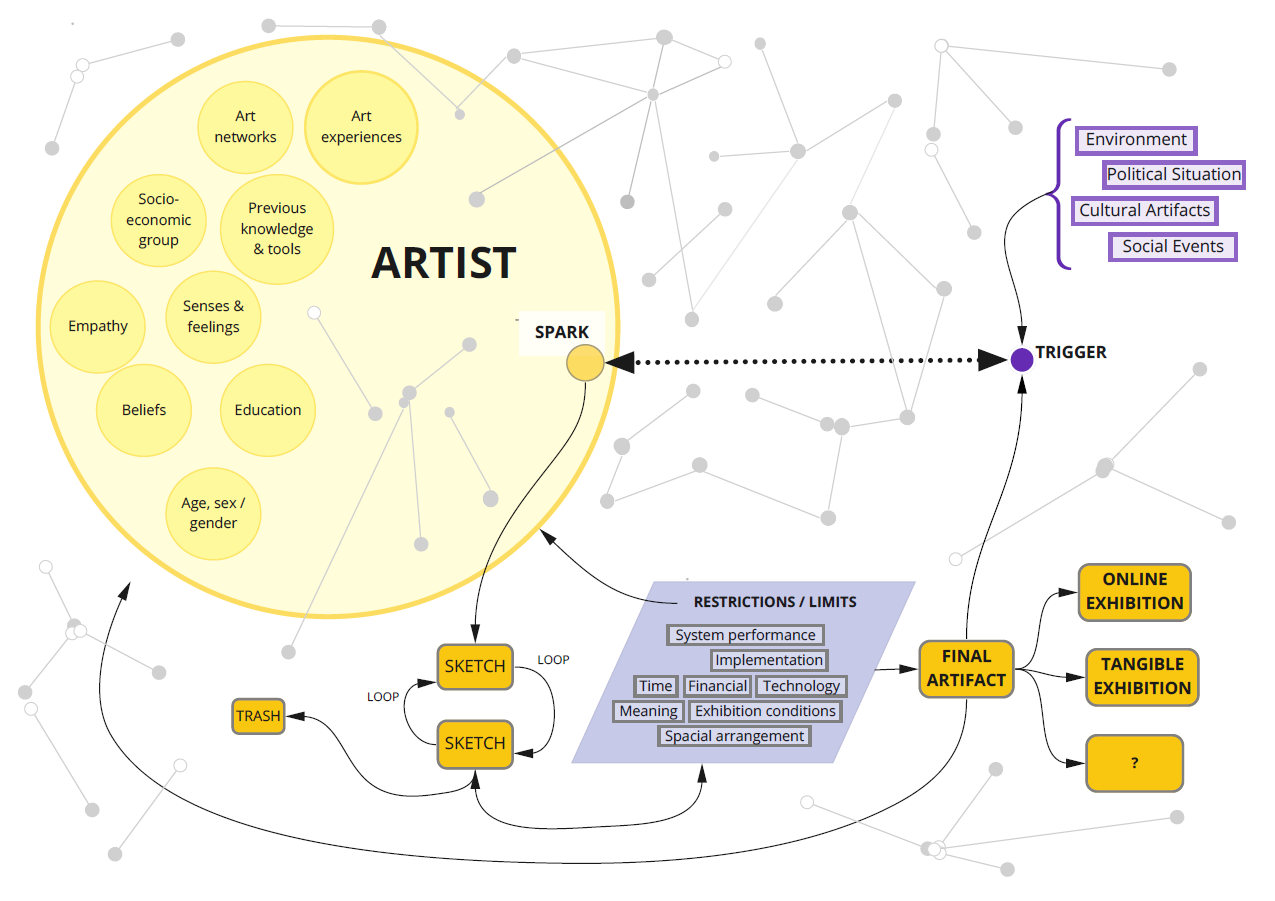

Many museums, curators, and artists seek new ways of connecting with audiences. What solutions can virtual space and digital technology offer? Can artistic collaboration thrive in virtual spaces? How can we deploy digital technology to unite and not divide us? A public event addressing these questions took place in spring 2021 in Seoul, deeply impressing me.

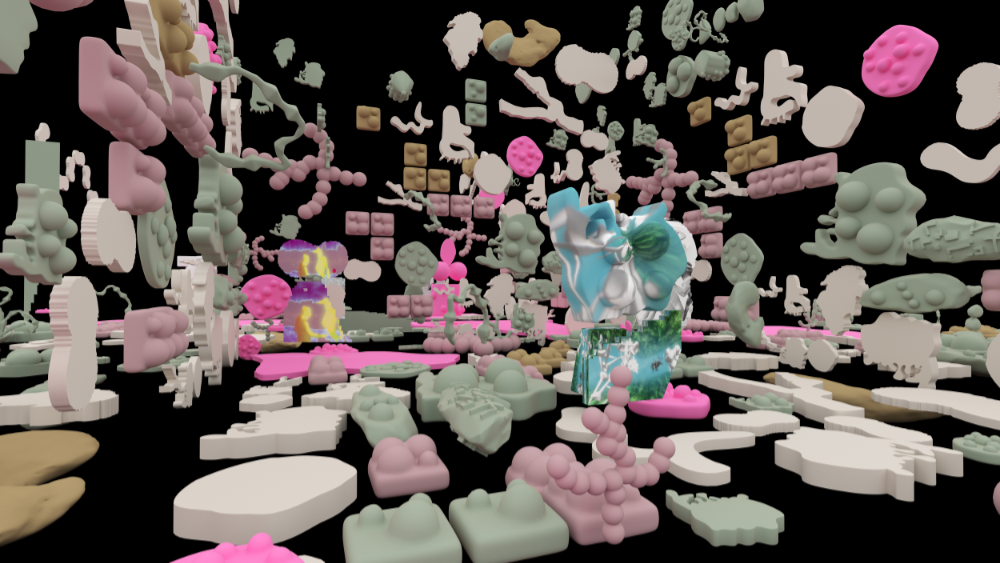

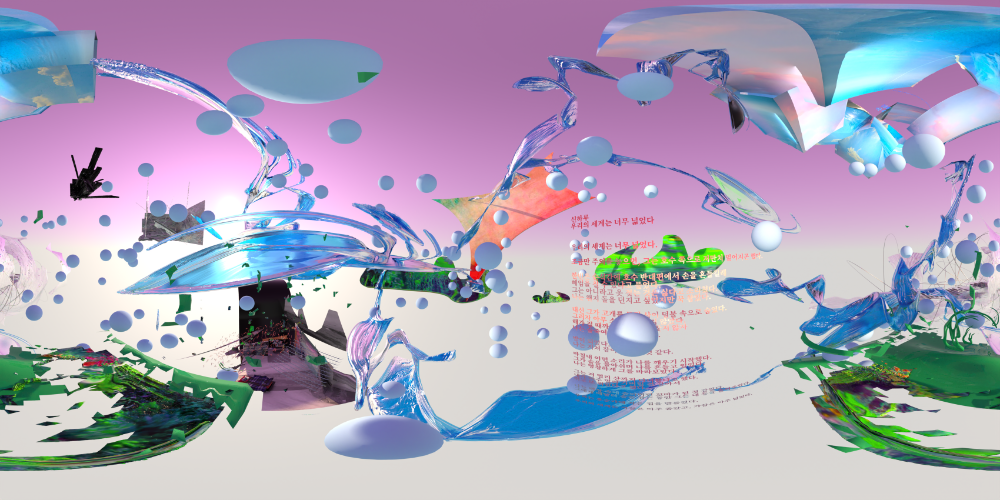

Erangel: Dark Tour[1] was held on an island called Erangel within the computer game PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds. A hundred random participants were invited to tour the island guided by three performers called Native, Immigrant, and Foreigner. In normal Battlegrounds gaming sessions, gamers would not have time to wander around the island while fighting each other to be the last survivor. However, the director requested participants enter the game not as combatants but as tourists, proposing a new rule: Stop shooting and stroll around and savour. Really? Could such collaboration among random audience members work? This time, it did. To hear more about this collaborative performance, I met Oh Youngjin, culture critic and associate professor of Korean Language and Literature at Hanhyang University Korea, who designed and organized Erangel: Dark Tour.

Seihee Shon: I wonder why you chose PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) above other multiplayer games.

Oh Youngjin: I considered many games but most of their fictional worlds are economically constructed to be just good enough for fun gameplay, whereas Battlegrounds has some sincerity in its design. For example, in Battlegrounds, unlike many other games, bullets have a parabolic trajectory. The physical laws in real life work here. The topographical features of Erangel are consistent and the details beyond what players can perceive, over an area equivalent to one-sixth that of Seoul. Initially, I thought, ‘This game has huge resources—perhaps we can use them differently. Who could do this? Maybe artists.’

SS: What was your primary purpose in organizing the performance?

OY: It was to emancipate the space. Game as a medium has great potential. But the design of most games is intended to stimulate particular behaviours. The landscapes of Erangel are beautiful. While playing Battlegrounds, I came up with questions like, ‘Why do we have to concentrate only on killing each other; why not just wander around?’ I thought the virtual space could be emancipated from being a ‘battlefield’ by drawing up a collective agreement among gamers to change the rules. It was crucial not to impose a new rule such as “Do not shoot each other” on gamers. I could have changed the game settings so weapons were not initially provided. But I didn’t. Voluntary participation is important. During the performance, weapons were allowed as normal, anyone could use them to attack others. It was simply that no one fired.

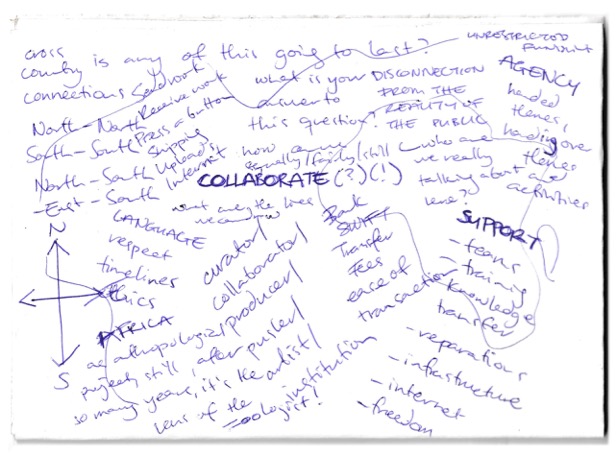

SS: In the artist talk, a member of the audience confessed that he had planned to throw a hand grenade but it failed due to a glitch on his network. I guess you had to take a risk and prepare for unpredictability, as much as giving participants considerable autonomy. What strategies and precautions did you introduce?

OY: My colleagues and I asked ourselves: ‘How do we want to welcome the audience into the game?’ Above all, we focussed on it being interactive. We rehearsed many times, making several scripts to accommodate probable situations. We agreed we should not be discouraged whatever happened. We cannot know the outcome when we throw the dice. It was a sort of countermeasure to run the tour in three groups. If an accident occurred in one group, people could move to another. We also had an audience watching livestreams of the performance. That day, it rained in reality and also in Erangel by chance; the weather in the game is random. This helped to raise the immersive level. I used sound effects to convey a sense of vitality in the game.

Erangel: Dark Tour encompasses performance, event, collaboration, livestreaming, and recording. I see a relationship between this experiment and Jacques Rancière’s principle of spectatorship in his book The Emancipated Spectator: “Being a spectator is not some passive condition that we should transform into activity. It is our normal situation.”[2] Rancière argues that we are all equally capable of interpreting and appropriating works for ourselves. Embracing collective creativity, Erangel: Dark Tour examines the subjectivity of participants and spectators and the aesthetics of participatory and collaborative work.

[1] Erangel: Dark Tour was part of a public art project Virtual Station held 5th-21st March 2021 in Seoul.

[2] Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2009), 17